An independent federal agency headed by three people who are nominated by the President and required by the Marine Mammal Protection Act to be knowledgeable in marine ecology and resource management, the Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) is responsible for overseeing the protection and conservation of marine mammals, making recommendations to various other government agencies, and awarding research grants.

The Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) was established in 1972 under Title II of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which came about in part as a result of growing concern among scientists and the public that some species and populations of marine mammals could face depletion, or even extinction, as a result of human activities. The Act, which was the first legislation anywhere in the world to mandate an ecosystem approach to marine resource management, set in motion a national policy to prevent marine mammal populations from diminishing due to human actions. It has been amended several times over the years. The amendments to the Marine Mammal Protection Act include: the Endangered Species Act, 1973; the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act, 1976, 1977, 1978; the Congressional Reports Elimination Act of 1980, 1981; the Fisheries Amendments of 1982, 1984, 1986; the Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments of 1988; the Fishery Conservation Amendments of 1990, 1992; the International Dolphin Conservation Act of 1992; the High Seas Driftnet Fisheries Enforcement Act, 1992; the Oceans Act of 1992, 1993, 1994; the Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments of 1994; the Fisheries Act of 1995, 1996, 1997; the Sustainable Fisheries Act, 1996; the International Dolphin Conservation Program Act, 1997, 1998, 1999; the Striped Bass Conservation, Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Management, the Marine Mammal Rescue Assistance Act of 2000, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 As Amended November 2001. In 1999, the MMC and other federal agencies with responsibilities under the Marine Mammal Protection Act began discussions to identify issues that they agreed deserved attention during Act reauthorizations, and to make recommendations for Congressional consideration. In 2008, no new reauthorization bill was submitted to Congress, pending appointments and priorities made by the incoming administration of Barack Obama. However, specific bills targeted at specific issues were introduced, including creation of an MMC-administered National Marine Mammal Research Program, establishment of fishing moratorium penalties, and polar bear importation. However, none of these bills was passed during that session of Congress.

One of commission’s most recent undertakings is an assessment of a 2011 National Park Service statistical analysis of potential displacement of harbor seal breeding by shellfish aquaculture at Point Reyes National Seashore.

The Marine Mammal Commission (MMC), along with its Committee of Scientific Advisors, reviews the programs, policies and funding of all federal agencies as they relate to marine mammals and determines what actions are needed to protect and conserve them. It formulates and promotes implementation of long-term specific procedures in recommendations to Congress, the Department of Commerce, the Department of the Interior, and other appropriate parties. The Commission devotes special attention to particular species and populations that are most at risk due to human-related activities, including marine mammals listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act, or as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, or those not yet listed, but threatened by a new conservation challenge.

Another priority of the MMC is minimizing the direct and indirect effects of chemical contaminants, debris, noise, and other forms of ocean pollution on marine mammals and other marine organisms. In addition, the Commission recommends measures it believes are desirable to further the policies of the Marine Mammal Act, including provisions for the protection of the Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts, whose livelihood may be adversely affected by actions taken because of it. The Commission also makes recommendations on activities pursuant to existing additional applicable laws, including the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, the Whaling Convention Act of 1949, the Interim Convention on the Conservation of North Pacific Fur Seals, and the Fur Seal Act of 1966.

Additionally, the Commission manages a small research program that includes putting on workshops, writing literature reviews, providing seed money for innovative or particularly promising research projects, and awarding grants based on proposals submitted in response to general and specific topic requests, the amounts varying from year to year depending upon the level of Congressional appropriations. Federal agencies are not required to adopt the recommendations made by the Commission, but the Marine Mammal Act does mandate that any agency that declines to follow them must provide a detailed written explanation within 120 days.

In February 2010, the MMC launched its review of the potential effects of human activities on harbor seals in Drake's Estero, an estuary within the Point Reyes National Seashore, in Marin County, California. A meeting of independent reviewers took place at Point Reyes to make presentations and share data, the results of which are available on the Drake’s Estero Commission Review page of the MMC Web site.

Following the April 10, 2010, explosion of the BP-leased Deepwater Horizon oil rig and resulting leak of 4.9 million barrels of oil in the Gulf of Mexico, the MMC undertook the monitoring of the disaster’s aftermath. Its work has involved tracking of response, assessment, and restoration efforts, as well as an assessment of the effects of the spill on the ecosystem, including marine mammals.

Reports of Interest

Collisions Between Ships and Whales (pdf)

Review of the Literature Pertaining to Swimming with Wild Dolphins (pdf)

Preliminary Evidence that Boat Speed Restrictions Reduce Deaths of Florida Manatees (pdf)

Behavioral responses of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, to gillnets and acoustic alarms (pdf)

Influence of Power Plants and Other Warm-Water Refuges on Florida Manatees (pdf)

Status of Protection Programs for Endangered, Threatened, and Depleted Marine Mammals in U.S. Waters (pdf)

Review of Harbor Seal and Human Interactions In Drake’s Estero California—Draft Terms of Reference (pdf)

U.S. Government Web site on Gulf of Mexico oil spill response and restoration activities

Wildlife Branch Summary Reports on stranded wildlife affected by the Gulf oil spill

MMC’s Recommendations for the Oil Spill Commission (pdf)

From the Web Site of the MMC

Marine Mammal Committee Testimony

Marine Mammal Species of Special Concern

In FY 2011, the Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) spent 99.7% of its $3,243,500 appropriated budget. Salaries and benefits received the lion’s share (60%) of those funds, 18% went to the science program, 19% was spent on administration and rent, and 3% on travel. In terms of the work performed by the agency, the commission reports that 75% of its annual funding is used to meet general oversight and advisory responsibilities, including stock assessment review, scientific research permits, incidental take authorizations, and the listing (or de-listing) of endangered species; the remaining 25% goes to workshops, special projects, and essential research.

Makah Ruling Upsets Environmentalists

The Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) upset anti-whaling activists in 2008 when it did not oppose an indigenous tribe’s request to resume hunting whales.

The Makah Tribe stopped hunting whales in the 1920s, when commercial whaling threatened to eradicate some species. With the recovery of the North Pacific gray whales, the tribe requested, and received approval, to resume whaling in 1999. It killed one whale that year, but was prevented from hunting more in subsequent years due to lawsuits filed by activists.

A draft of an environmental impact statement prepared to assess the tribe’s request produced little comment from the MMC, which can only advise on such matters.

Still, environmentalists were incensed that the MMC did not bother to comment on the Makah’s plans. It merely said the environmental impact statement met the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act. Early in 2012, the federal government scrapped the draft of the environmental impact study, promising that another impact statement would be prepared based on new scientific data. So, years later, the tribe is still awaiting a decision.

U.S. Halts Makah Whaling Study after Seven Years over “New Scientific Information” (by Paul Gottlieb, Peninsula Daily News)

Marine Mammal Commission Declines To Comment on Makah Whaling; Activists Fume (by Jim Casey, Peninsula Daily News)

Makah Tribal Whale Hunt (Northwest Regional Office)

Court to Reexamine Environmental Impact of Controversial Makah Whale Hunt (Cultural Survival)

MMC Falls Behind on Report

The MMC was tagged with ratings “Incomplete” and “Unsatisfactory” for its handling of special projects mandated by Congress. In 2009, it was supposed to deliver a report on the ecological role of killer whales, which it failed to do. It promised to issue the report in 2010. Again, it did not, claiming it was too busy working on the effects of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The commission then hired a killer whale expert to help the MMC complete the report.

In March 2011, a conservation group, The Orca Project, criticized the federal government’s recordkeeping in regards to killer whales. The group said an audit of Marine Mammal Inventory Reports revealed “shockingly sparse data” on the whales. Despite 40 years of tracking marine mammals, less than 2% of the data had to do with killer whales.

NOAA-NMFS Failures in Marine Mammal Inventory Management for Killer Whales (The Orca Project)

- Table of Contents

- Overview

- History

- What it Does

- Where Does the Money Go

- Controversies

- Suggested Reforms

- Comments

- Leave a comment

Daryl J. Boness, nominated on January 19, 2010, by President Barack Obama to be the next chairman of the Marine Mammal Commission, is a retired scientist who spent most of his career working at the National Zoo and studying seals, sea lions and walruses.

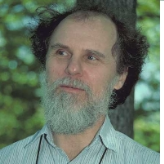

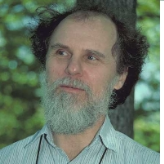

John E. Reynolds III, was named Chairman of the Marine Mammal Commission by George H. W. Bush in 1991. Reynolds received a B.A.in Biology from Western Maryland College in 1974; an M.S.in Biological Oceanography from the University of Miami-Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Miami, in 1977; and a Ph.D in Biological Oceanography from the University of Miami - School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Miami, in 1980. That same year, he became an Assistant Professor of Biology and Marine Science at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida, and Chairman of Natural Sciences at Eckerd from 1986 to 1992. He has also been a professor at the University of South Florida; a visiting professor at Duke University Marine Laboratory; and has taught outreach courses in Cell Biology and Marine Mammology for high school students. He is also a referee for manuscripts submitted to the Marine Mammal Science and Florida Scientist; reviewer for proposals for the National Science Foundation; and a Member of the Scientific Advisory Committee for Save the Manatee Club. Reynolds has also received more than 20 research grants and written or co-written several books, as well as articles for more than 120 publications, predominantly on marine mammals and biology. Currently, Reynolds is the Director of the Center for Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Research at Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida.

- Latest News

- D.C. Public Schools will Teach all Second-Graders to Ride a Bike

- New Rule in Germany Limits Sales of Sex-Themed E-Books to 10pm to 6am

- What Happened to the 6-Year-Old Tibetan Boy the Chinese Government Kidnapped 20 Years Ago?

- U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Photoshops his Hair Color to Mock Turkish Mayor

- Mystery Artist Calls Attention to Unfixed Potholes by Drawing Penises around Them

An independent federal agency headed by three people who are nominated by the President and required by the Marine Mammal Protection Act to be knowledgeable in marine ecology and resource management, the Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) is responsible for overseeing the protection and conservation of marine mammals, making recommendations to various other government agencies, and awarding research grants.

The Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) was established in 1972 under Title II of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which came about in part as a result of growing concern among scientists and the public that some species and populations of marine mammals could face depletion, or even extinction, as a result of human activities. The Act, which was the first legislation anywhere in the world to mandate an ecosystem approach to marine resource management, set in motion a national policy to prevent marine mammal populations from diminishing due to human actions. It has been amended several times over the years. The amendments to the Marine Mammal Protection Act include: the Endangered Species Act, 1973; the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act, 1976, 1977, 1978; the Congressional Reports Elimination Act of 1980, 1981; the Fisheries Amendments of 1982, 1984, 1986; the Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments of 1988; the Fishery Conservation Amendments of 1990, 1992; the International Dolphin Conservation Act of 1992; the High Seas Driftnet Fisheries Enforcement Act, 1992; the Oceans Act of 1992, 1993, 1994; the Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments of 1994; the Fisheries Act of 1995, 1996, 1997; the Sustainable Fisheries Act, 1996; the International Dolphin Conservation Program Act, 1997, 1998, 1999; the Striped Bass Conservation, Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Management, the Marine Mammal Rescue Assistance Act of 2000, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 As Amended November 2001. In 1999, the MMC and other federal agencies with responsibilities under the Marine Mammal Protection Act began discussions to identify issues that they agreed deserved attention during Act reauthorizations, and to make recommendations for Congressional consideration. In 2008, no new reauthorization bill was submitted to Congress, pending appointments and priorities made by the incoming administration of Barack Obama. However, specific bills targeted at specific issues were introduced, including creation of an MMC-administered National Marine Mammal Research Program, establishment of fishing moratorium penalties, and polar bear importation. However, none of these bills was passed during that session of Congress.

One of commission’s most recent undertakings is an assessment of a 2011 National Park Service statistical analysis of potential displacement of harbor seal breeding by shellfish aquaculture at Point Reyes National Seashore.

The Marine Mammal Commission (MMC), along with its Committee of Scientific Advisors, reviews the programs, policies and funding of all federal agencies as they relate to marine mammals and determines what actions are needed to protect and conserve them. It formulates and promotes implementation of long-term specific procedures in recommendations to Congress, the Department of Commerce, the Department of the Interior, and other appropriate parties. The Commission devotes special attention to particular species and populations that are most at risk due to human-related activities, including marine mammals listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act, or as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, or those not yet listed, but threatened by a new conservation challenge.

Another priority of the MMC is minimizing the direct and indirect effects of chemical contaminants, debris, noise, and other forms of ocean pollution on marine mammals and other marine organisms. In addition, the Commission recommends measures it believes are desirable to further the policies of the Marine Mammal Act, including provisions for the protection of the Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts, whose livelihood may be adversely affected by actions taken because of it. The Commission also makes recommendations on activities pursuant to existing additional applicable laws, including the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, the Whaling Convention Act of 1949, the Interim Convention on the Conservation of North Pacific Fur Seals, and the Fur Seal Act of 1966.

Additionally, the Commission manages a small research program that includes putting on workshops, writing literature reviews, providing seed money for innovative or particularly promising research projects, and awarding grants based on proposals submitted in response to general and specific topic requests, the amounts varying from year to year depending upon the level of Congressional appropriations. Federal agencies are not required to adopt the recommendations made by the Commission, but the Marine Mammal Act does mandate that any agency that declines to follow them must provide a detailed written explanation within 120 days.

In February 2010, the MMC launched its review of the potential effects of human activities on harbor seals in Drake's Estero, an estuary within the Point Reyes National Seashore, in Marin County, California. A meeting of independent reviewers took place at Point Reyes to make presentations and share data, the results of which are available on the Drake’s Estero Commission Review page of the MMC Web site.

Following the April 10, 2010, explosion of the BP-leased Deepwater Horizon oil rig and resulting leak of 4.9 million barrels of oil in the Gulf of Mexico, the MMC undertook the monitoring of the disaster’s aftermath. Its work has involved tracking of response, assessment, and restoration efforts, as well as an assessment of the effects of the spill on the ecosystem, including marine mammals.

Reports of Interest

Collisions Between Ships and Whales (pdf)

Review of the Literature Pertaining to Swimming with Wild Dolphins (pdf)

Preliminary Evidence that Boat Speed Restrictions Reduce Deaths of Florida Manatees (pdf)

Behavioral responses of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, to gillnets and acoustic alarms (pdf)

Influence of Power Plants and Other Warm-Water Refuges on Florida Manatees (pdf)

Status of Protection Programs for Endangered, Threatened, and Depleted Marine Mammals in U.S. Waters (pdf)

Review of Harbor Seal and Human Interactions In Drake’s Estero California—Draft Terms of Reference (pdf)

U.S. Government Web site on Gulf of Mexico oil spill response and restoration activities

Wildlife Branch Summary Reports on stranded wildlife affected by the Gulf oil spill

MMC’s Recommendations for the Oil Spill Commission (pdf)

From the Web Site of the MMC

Marine Mammal Committee Testimony

Marine Mammal Species of Special Concern

In FY 2011, the Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) spent 99.7% of its $3,243,500 appropriated budget. Salaries and benefits received the lion’s share (60%) of those funds, 18% went to the science program, 19% was spent on administration and rent, and 3% on travel. In terms of the work performed by the agency, the commission reports that 75% of its annual funding is used to meet general oversight and advisory responsibilities, including stock assessment review, scientific research permits, incidental take authorizations, and the listing (or de-listing) of endangered species; the remaining 25% goes to workshops, special projects, and essential research.

Makah Ruling Upsets Environmentalists

The Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) upset anti-whaling activists in 2008 when it did not oppose an indigenous tribe’s request to resume hunting whales.

The Makah Tribe stopped hunting whales in the 1920s, when commercial whaling threatened to eradicate some species. With the recovery of the North Pacific gray whales, the tribe requested, and received approval, to resume whaling in 1999. It killed one whale that year, but was prevented from hunting more in subsequent years due to lawsuits filed by activists.

A draft of an environmental impact statement prepared to assess the tribe’s request produced little comment from the MMC, which can only advise on such matters.

Still, environmentalists were incensed that the MMC did not bother to comment on the Makah’s plans. It merely said the environmental impact statement met the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act. Early in 2012, the federal government scrapped the draft of the environmental impact study, promising that another impact statement would be prepared based on new scientific data. So, years later, the tribe is still awaiting a decision.

U.S. Halts Makah Whaling Study after Seven Years over “New Scientific Information” (by Paul Gottlieb, Peninsula Daily News)

Marine Mammal Commission Declines To Comment on Makah Whaling; Activists Fume (by Jim Casey, Peninsula Daily News)

Makah Tribal Whale Hunt (Northwest Regional Office)

Court to Reexamine Environmental Impact of Controversial Makah Whale Hunt (Cultural Survival)

MMC Falls Behind on Report

The MMC was tagged with ratings “Incomplete” and “Unsatisfactory” for its handling of special projects mandated by Congress. In 2009, it was supposed to deliver a report on the ecological role of killer whales, which it failed to do. It promised to issue the report in 2010. Again, it did not, claiming it was too busy working on the effects of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The commission then hired a killer whale expert to help the MMC complete the report.

In March 2011, a conservation group, The Orca Project, criticized the federal government’s recordkeeping in regards to killer whales. The group said an audit of Marine Mammal Inventory Reports revealed “shockingly sparse data” on the whales. Despite 40 years of tracking marine mammals, less than 2% of the data had to do with killer whales.

NOAA-NMFS Failures in Marine Mammal Inventory Management for Killer Whales (The Orca Project)

Comments

Daryl J. Boness, nominated on January 19, 2010, by President Barack Obama to be the next chairman of the Marine Mammal Commission, is a retired scientist who spent most of his career working at the National Zoo and studying seals, sea lions and walruses.

John E. Reynolds III, was named Chairman of the Marine Mammal Commission by George H. W. Bush in 1991. Reynolds received a B.A.in Biology from Western Maryland College in 1974; an M.S.in Biological Oceanography from the University of Miami-Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Miami, in 1977; and a Ph.D in Biological Oceanography from the University of Miami - School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Miami, in 1980. That same year, he became an Assistant Professor of Biology and Marine Science at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida, and Chairman of Natural Sciences at Eckerd from 1986 to 1992. He has also been a professor at the University of South Florida; a visiting professor at Duke University Marine Laboratory; and has taught outreach courses in Cell Biology and Marine Mammology for high school students. He is also a referee for manuscripts submitted to the Marine Mammal Science and Florida Scientist; reviewer for proposals for the National Science Foundation; and a Member of the Scientific Advisory Committee for Save the Manatee Club. Reynolds has also received more than 20 research grants and written or co-written several books, as well as articles for more than 120 publications, predominantly on marine mammals and biology. Currently, Reynolds is the Director of the Center for Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Research at Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida.

- Latest News

- D.C. Public Schools will Teach all Second-Graders to Ride a Bike

- New Rule in Germany Limits Sales of Sex-Themed E-Books to 10pm to 6am

- What Happened to the 6-Year-Old Tibetan Boy the Chinese Government Kidnapped 20 Years Ago?

- U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Photoshops his Hair Color to Mock Turkish Mayor

- Mystery Artist Calls Attention to Unfixed Potholes by Drawing Penises around Them

Comments