U.S. Faces Uphill Task in Connecting With Modi Govt

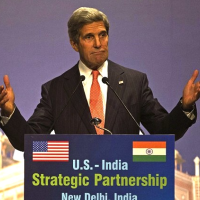

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry (file photo: Reuters)

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry (file photo: Reuters)

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry is in Delhi this week as Washington tries to reset ties with India, a country it sees as a counterbalance in Asia to China's rising power. But immediate results are unlikely as the U.S. has some catching up to do with the other countries vying for the new administration’s attention.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected in May, the U.S. found it had to do business with a leader to whom it had denied a visa in 2005 over anti-Muslim riots that had taken place in Gujarat in 2002 when he was chief minister. That was fine as long as Modi remained a chief minister. But once he was announced as the BJP’s candidate for prime minister last September, the U.S. found it had no way of mending fences, particularly since then U.S. Ambassador Nancy Powell still resisted meeting Modi. Her stance looked untenable once the UK High Commissioner and European ambassadors ended the informal ban and met with the man who could become the next Prime Minister of India.

Even when Powell requested a meeting, Modi made her wait for a month before he met her. She also had to travel to Gandhinagar to meet him at his chief minister’s office. While the meeting was cordial and Modi greeted her with a bouquet of flowers, it was clear that the U.S. was not a priority.

And so, once Modi was elected with a decisive mandate, the foreign ministers of China, France, UK and Russia all visited New Delhi to meet the new administration. The western countries are particularly keen on building strong defence ties, while China and Russia would like India on their side (or remain neutral) in their respective stand-offs with the West.

Modi, on his part, has indicated that his first priority is rebuilding India’s sluggish economy from the mess he inherited from the previous UPA administration. His biggest foreign policy mission is rebuilding India’s ties with its neighbours and his invitation to all South Asian heads of state to attend his swearing in ceremony in New Delhi in May was a masterstroke. He has since visited Bhutan and will visit Nepal next on August 3-4.

So the U.S. finds itself in an awkward position in dealing with the world’s biggest democracy. This is unfortunate since both countries are natural allies: they are democracies, both are targets of Islamic terrorism, and both are worried about China’s rise. Yet in South Asia, like in the rest of the world, respect and personal ties between leaders are important. And that is where the U.S. president has to start from scratch, since no senior official in his administration has dealt with Modi.

Barack Obama rightly invited Modi after his victory to the White House when the Indian leader visits the U.S. for the U.N. General Assembly in September. But that is almost two months away, so the U.S. administration decided to have the fifth annual India-US Strategic Dialogue in Delhi even though it was Washington’s turn to host it – just so that Kerry could meet Modi personally.

There are likely to be many nice speeches and much bonhomie in public this week, but the U.S side will find that Modi’s administration is not likely to change its position on protective tariffs, the WTO trade deal, or combating climate change merely because the U.S. would like it to do. Similarly, New Delhi is not likely to toe Washington’s line on Beijing merely because the U.S. wants to make India a counterweight to China. India can be expected to formulate its own policies keeping its own national interests in mind.

It is up to Kerry and his team to make a start by convincing the Indian administration that they are equal partners for the long-term. That would be the best possible foundation at this stage, leaving the real breakthrough for the White House meeting in September.

- Karan Singh

- Top Stories

- Controversies

- Where is the Money Going?

- India and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Unusual News

- Latest News

- India College Chain’s Expansion into U.S. Draws Opposition from Massachusetts Officials over Quality of Education

- Milk Shortages in India Tied to Release of New Movies Featuring Nation’s Favorite Stars

- Confusion Swirls around Kashmir Newspaper Ban in Wake of Violent Street Protests

- Polio-Free for 5 Years, India Launches Vaccine Drive after Polio Strain Discovery

- New Aviation Policy Could Increase Service, Lower Ticket Prices

Comments