Desegregation Orders for Scores of U.S. School Districts Have Been Ignored for Decades

Who dropped the ball on school desegregation?

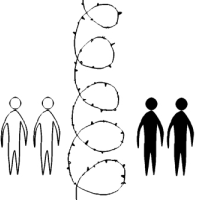

If the course of desegregating American public schools for the past 50 years were mapped on a graph, it would resemble a bell-shaped curve. The first 20 years, during the 1960s and 1970s, would reveal a steady climb upwards as hundreds of school districts, primarily in the South, were ordered by federal courts to integrate their black and white student populations. But beginning in the 1980s and continuing through to now, the courts’ and the federal government’s interest in keeping desegregation out of schools has waned considerably, resulting in “scores” of orders being ignored by local school officials, according to an investigation by ProPublica.

Following the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (pdf), desegregation moved at a rapid pace. In about 10 years, the South went from having 1% of black children attend schools with whites to 90% by the early 1970s. Desegregation orders also were imposed on school districts throughout the country, ProPublica noted.

But now “this once-powerful force is in considerable disarray,” reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote.

ProPublica used academic studies and legal databases, and contacted more than 160 school districts across the U.S., to create a comprehensive study of the nation’s active desegregation orders. What it found was “a world of confusion, neglect and inaction.”

The investigation discovered that many school districts no longer pay attention to their desegregation orders, even though they are still in effect. Officials “have never read them, or erroneously believe that orders have been ended. In many cases, orders have gone unmonitored, sometimes for decades, by the federal agencies charged with enforcing them,” Hannah-Jones reported.

It is estimated that more than 300 school districts still face active desegregation orders.

But in many instances, no action is being taken.

The federal courts often seem checked out when it comes to enforcing desegregation orders. Hannah-Jones says, “With increasing frequency, federal judges are releasing districts from court oversight even where segregation prevails, at times taking the lack of action in cases as evidence that the problems have been resolved.”

While it provided ProPublica with a list of active desegregation orders, the U.S. Department of Justice would not allow any of its officials to be interviewed on the subject, nor would it respond to a dozen written questions about how it monitors and enforces desegregation cases.

The U.S. Department of Education, under whose direction the Office of Civil Rights monitors desegregation efforts, also refused for its officials to be interviewed.

During its investigation ProPublica found that, in some instances, active desegregation orders had not only been ignored, but were shipped back to Washington to be boxed up in the federal archives.

“Across the country, original court orders and their underlying records have been destroyed by fire, shipped to a central archive center, or lost in the dusty parchment graveyards of courthouse basements,” wrote Hannah-Jones. “Some orders have lain dormant for so long that everyone involved, including judges and lawyers, are either retired or dead.”

How did the country go from rigorously integrating schools to largely not caring?

Starting with the Reagan administration, the U.S. Justice Department backed off on forcing integration in schools. William Bradford Reynolds, the head of the Justice Department's civil rights division under Reagan, said the department would not “compel children who do not want to choose to have an integrated education to have one,” according to ProPublica.

Things continued in this direction under President George W. Bush, and in between these two Republican administrations, the U.S. Supreme Court made it more difficult for parents and others to challenge racial inequities in schools by having to prove school officials are intentionally discriminating against black and Hispanic students.

-Noel Brinkerhoff, Danny Biederman

To Learn More:

Lack of Order: The Erosion of a Once-Great Force for Integration (by Nikole Hannah-Jones, ProPublica)

Desegregation Court Records (by Nikole Hannah Jones, ProPublica)

Study Finds Increasing School Segregation Based on Race and Economic Class (by Matt Bewig, AllGov)

U.S. Accuses Meridian, Mississippi, in First “School-to-Prison Pipeline” Lawsuit (by Noel Brinkerhoff, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments