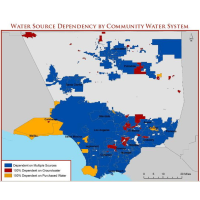

75% of L.A. County Drinking Water Systems Are at Risk

(map: Luskin Center for Innovation at UCLA)

(map: Luskin Center for Innovation at UCLA)

Upon review, it was not a good idea to allow much of the groundwater in Los Angeles County to become contaminated. Decades of water wars in the state clearly evidenced the critical need for drinkable water by the 1980s, when the region’s contamination became too overbearing and the effort intensified to find water elsewhere and pipe it in.

A new study (pdf) by the Luskin Center for Innovation at UCLA identifies several important threats to the county’s water systems and literally provides maps of the complex systems just in case the state ever decides to develop a comprehensive plan for dealing with the drought.

Los Angeles County is served by 228 government and private community water systems. Seventy-five percent of them suffer from at least one vulnerability sufficient to put its users at risk. That includes “dependency on a single type of water source, local groundwater contamination, small size, or a projected increase in extreme heat days over the coming decades.”

That last one would seem to cover all the water systems.

“Los Angeles County Community Water Systems: Atlas and Policy Guide Volume I” uses a series of charts and maps to profile 213 of the water systems based on their sources, service populations and superstructures.

The study found that more than a third of the systems (79) were 100% reliant on groundwater. Most of these systems serve small communities in the more rural, northern part of the county, where groundwater withdrawal is not regulated and highly vulnerable to overpumping in times of drought.

Nearly 100 systems are so small, serving less than 3,300 residents, that they do not have the “technical, managerial, and financial capacity to withstand the impact of severe drought conditions.”

Azusa, Covina, and El Monte can expect 30 more days a year of temperatures over 95 by 2050, making their “increasing water demand for residential landscapes, public green spaces, and agricultural uses” problematic—“if they are retained.”

No county in the state is more reliant than L.A. on groundwater that has been deemed contaminated at one time or another. “Forty percent of community providers in LA County got their water from a groundwater source that exceeded drinking water Maximum Contaminant Levels at least once over the period of 2002-2010,” the report says.

That could be a blessing in disguise, albeit an expensive and disgusting one. “Most Large and Very Large community water systems serving LA County have at least partial reliance on contaminated groundwater sources,” according to the report, and by virtue of their size may have the resources to build plants to treat the water. The study uses an estimate that it would cost $600 million to $900 million to transform the San Fernando Valley aquifer, half of which is contaminated by a toxic plume, into a “reliable water source.”

That’s an option not available to the majority of the county’s water systems, which are small. The study muses over the possibility of larger systems adopting smaller systems and notes that the state is providing funds for interim emergency drinking water. But it’s clear, the report says, “Without a strong fiscal base to draw on, smaller water systems will struggle to adapt to a changing climate.”

–Ken Broder

To Learn More:

Groundwater Contamination a Growing Problem in L.A. County Wells (by Rong-Gong Lin II and Priya Krishnakumar, Los Angeles Times)

75 Percent of Community Water Systems in Los Angeles County Exhibit Vulnerability to Drought and Other Supply Challenges (Luskin Center for Innovation at UCLA)

NASA Scientist Says California Has One Year of Water Reserves Left (by Ken Broder, AllGov California)

Los Angeles County Community Water Systems: Atlas and Policy Guide Volume I (by J.R. DeShazo and Henry McCann, Luskin Center for Innovation at UCLA) (pdf)

- Top Stories

- Controversies

- Where is the Money Going?

- California and the Nation

- Appointments and Resignations

- Unusual News

- Latest News

- California Forbids U.S. Immigration Agents from Pretending to be Police

- California Lawmakers Urged to Strip “Self-Dealing” Tax Board of Its Duties

- Big Oil’s Grip on California

- Santa Cruz Police See Homeland Security Betrayal in Use of Gang Roundup as Cover for Immigration Raid

- Oil Companies Face Deadline to Stop Polluting California Groundwater