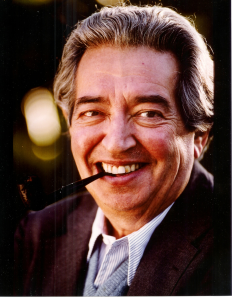

On March 19, 2016, the popular novelist Irving Wallace—my father—would have turned 100 years old. Instead of honoring my father by presenting a review of his achievements and recalling what a generous, warm-hearted person he was and how much enjoyment he brought to millions of readers around the world, I have decided to look at some of the developments he would have most appreciated if he had lived to be 100, instead of dying at the age of 74.

It may seem overly speculative to imagine my father living to 100. However, just ten days earlier, on March 9, 2016, I conducted an extended video interview with a 102-year-old man, Alex Tarics. The interview was part of a project called Words of Olympians, supported by the International Olympic Committee. Mr. Tarics earned a gold medal in water polo at the 1936 Olympics and also was a well-respected structural engineer. As I sat across from Mr. Tarics for several hours, the idea that my father could have reached the age of 100 did not seem at all impossible.

So what did my father miss?

The most obvious development was the election of an African-American president. You see, back in 1964 my father wrote a novel, The Man, about the first black president. His protagonist, Douglass Dilman, is a retired university president who enters politics and unexpectedly becomes president when the people ahead of him in the line of succession die. (After the publication of The Man, the 25th Amendment was passed, giving the president the right to fill a vice-presidential vacancy.) My father received death threats for suggesting such a possibility, and one evening a white man telephoned our house saying he was coming over to kill my father. He was headed off before he arrived.

On the night of the 2008 election, friends and family gathered at my house to watch the results. When it was announced that Barack Obama had won, many people (including me) were moved to tears. I was so proud of my father for having brought to the public attention the idea that a black citizen could become president at a time when such a concept was unheard of. My father had received death threats for creating a fictional black president and now, 18 years after my father’s death, the American people had elected an African-American president. I cannot even imagine my father’s emotions had he lived to see that day.

My father would have been pleased to learn that the spirit of The Man continues. For example, the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg is currently exhibiting the work of the Chilean-born artist Alfredo Jaar, who has stated that one of these works was inspired by The Man.

My father would also have enjoyed the fact that the Australian hip-hop duo Spit Syndicate named one of their albums, Sunday Gentlemen, after another of my father’s books: The Sunday Gentleman. My father had created that title because, as a struggling young (and middle-aged) writer, he wrote for others six days a week and then, on Sundays, he wrote what he wanted.

The first time I became aware that my father had missed something by dying was the introduction of bookstores with chairs, couches and food. He loved browsing in bookstores. The idea that he could have relaxed and grabbed a bite to eat while doing so would have thrilled him.

My father was interested in such a wide range of subjects that it’s hard to grasp. He compiled a personal library of 35,000 volumes, and few activities pleased him more than to burrow into his library, starting with one subject and then being led to another and another and another. Imagine if he had lived long enough to enjoy the Age of the Internet. It would have been more than a dream come true because he could not have dreamt it.

He was also obsessed with trying out the latest gadgets. He would have loved digital cameras that allow you to review your photos immediately without waiting for a lab to develop your film. And smartphones? My father collected small cameras. To have one always on hand that also serves as a telephone and a detailed map of the world and a notepad and more? Wow. Once smartphones became enabled with fast and reliable Internet service, he would have appreciated them (as I do now) as an encyclopedia in your pocket.

And speaking of “gadgets,” he would have bought or leased a Tesla. An American-made luxury electric car: what could be better?

One more development my father would have enjoyed enormously: Woody Allen’s film Midnight in Paris.

Of course, had he lived to 100, my father would have experienced some sad events, most notably the death of his wife, Sylvia; his sister, Esther; and the premature death of his beloved daughter, Amy.

But he would have also delighted in watching his grandsons, Elijah and Aaron, grow up. He would have attended their soccer matches and he would have been greatly pleased to learn that they inherited his love of gadgets and technological advancements. It would have brought him joy to see that my wife, Flora, and I decided to raise them for part of their childhoods in France.

At the time that we moved to France, we had no idea that he had wanted to raise me there. After my mother died in 2006, I discovered two boxes of correspondence between her and my father. When I was 17 months old, my father was working in Paris, and he sent my mother, back in California, a series of letters trying to convince her (unsuccessfully) to move to Paris. He even sent her newspaper ads for an English-language diaper service.

I said that I wouldn’t deal with my father’s achievements, but when I think of my father's legacy, I think of a quotation from the final page of his novel The Prize, the last line of which appears on his grave marker:

“All man's honors are small beside the greatest prize to which he may and must aspire—the finding of his soul, his spirit, his divine strength and worth—the knowledge that he can and must live in freedom and dignity—the final realization that life is not a daily dying, not a pointless end, not ashes-to-ashes and dust-to-dust, but a soaring and blinding gift snatched from eternity.”

David Wallechinsky