Being Poor Is Treated Like a Crime in Some Parts of U.S.

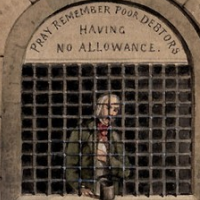

A debtor in London’s Fleet Street Prison, early 19th century (graphic: Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, Wikimedia)

A debtor in London’s Fleet Street Prison, early 19th century (graphic: Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, Wikimedia)

Nicholas Kristof, © 2016 New York Times News Service

TULSA, Okla. — In the 1830s, the civilized world began to close debtors’ prisons, recognizing them as barbaric and also silly: The one way to ensure that citizens cannot repay debts is to lock them up.

In the 21st century, the United States has reinstated a broad system of debtors’ prisons, in effect making it a crime to be poor.

If you don’t believe me, come with me to the county jail in Tulsa. On the day I visited, 23 people were incarcerated for failure to pay government fines and fees, including one woman imprisoned because she couldn’t pay a fine for lacking a license plate.

I sat in the jail with Rosalind Hall, 53, a warm, mild-mannered woman with graying hair who has been imprisoned for a total of almost 18 months, in short stints, simply for failing to pay a blizzard of fines and fees relating to petty crimes (for which she separately served time). Hall has struggled for three decades with mental illness and drug addictions and has a long history of shoplifting to pay for drugs, but no violent record.

Tears welled in her eyes as she told how she was trying to turn her life around, no longer stealing, and steering clear of drugs for the last two years — but her fines and fees keep increasing and now total $11,258. With depression and bipolar disorder, she has little hope of getting a regular job, so she is periodically arrested for failing to pay.

This time, she had already spent 10 days in jail for failing to pay restitution for five bad checks written eight years ago to a grocery store. The bad checks totaled a bit more than $100, but with fees and charges added on she still owes $1,200 in restitution on them — and that’s after eight years of making payments.

“If I can’t afford to pay it, how can I pay it?” Hall asked me, as we sat in a visiting room in the jail. “I can’t do it.”

Hall survives on food stamps, castoff clothes provided by churches, a friend’s willingness to give her a room, and $50 a month she earns by cleaning a woman’s house. She allocates $40 to paying restitution, leaving her just $10 a month in cash for her and her beloved puppy (whom her neighbor looks after whenever she’s jailed for debts).

“It’s 100 percent true that we have debtor prisons in 2016,” says Jill Webb, a public defender. “The only reason these people are in jail is that they can’t pay their fines.

“Not only that, but we’re paying $64 a day to keep them in jail — not because of what they’ve done, but because they’re poor.”

This is as unconscionable in 2016 as it was in 1830, and it is a system found across the country. In the last 25 years, as mass incarceration became increasingly costly, states and localities shifted the burden to criminal offenders with an explosion in special fees and surcharges. Here in Oklahoma, criminal defendants can be assessed 66 different kinds of fees, from a “courthouse security fee” to a “sheriff’s fee for pursuing fugitive from justice,” and even a fee for an indigent person applying for a public defender (I’m not kidding: An indigent person is actually billed for requesting a public defender, and if he or she does not pay, an arrest warrant is issued).

Even the Tulsa County district attorney, Stephen Kunzweiler, thinks these fines are a ridiculous way to finance his office. “It’s a dysfunctional system,” he says.

A new book, “A Pound of Flesh,” by Alexes Harris of the University of Washington, notes that these modern debtors’ prisons exist across America. Harris writes that in Rhode Island in 2007, 18 people were incarcerated a day, on average, for failure to pay court debt, while in Ferguson, Missouri, the average household paid $272 in fines in 2012, and the average adult had 1.6 arrest warrants issued that year.

“Impoverished defendants have nothing to give,” Harris says, and the result is a system that disproportionately punishes the poor and minorities, leaving them with an overhang of debt from which they can never escape.

The Supreme Court has ruled that people should be jailed only when they refuse to pay, not when they can’t, and in theory safeguards protect the indigent. In practice those safeguards are chimerical, and the poor are routinely jailed for being poor. The way forward is to curb these fees, end the use by courts of private collection companies that add their own charges to the debt, and limit court debt to some percentage of a person’s income.

For now, some of the sums owed are staggering. Job Fields III told me he owes $70,000 in fees and fines. “It seems impossible,” he said, “but I’ve got to think positive.” Cynthia Odom told me she owes $170,000 and constantly struggles with whether to pay the electricity bill, buy food for her two kids, or pay down the debt and stay out of jail.

When kids are affected like that, as they often are, this system of jailing people who can’t pay fines is grotesque as well as Kafkaesque.

Amanda Goleman, 29, grew up in a meth house and began taking illegal drugs at 12, and her education wound down after she became pregnant in the ninth grade. For a time, she and her daughter were homeless.

But Goleman has turned herself around. She has had no offenses for almost four years and has been drug-free for three. For the last year, by her account and her employer’s, she has held a steady job in which she has been promoted — but she is still a single mom and struggles to pay old fines while also raising her three children, ages 2, 10 and 13.

“It’s either feed my kids or pay the fines,” Goleman said, “but if I don’t pay then I get a warrant.” Four times she has been arrested and jailed for a few days for being behind in her payments; each time, this created havoc with her children and posed challenges for keeping a job.

Webb thinks that these modern debtors’ prisons are so punitive that the underlying motivation is to stigmatize and punish the poor. “It hurts their families, it doesn’t make us safer, it’s expensive,” she says. “I can’t think of another reason other than animosity toward the poor.”

To Learn More:

Debtor’s Prison Charges Leveled at Austin, Texas (by Noel Brinkerhoff and Steve Straehley, AllGov)

Debtors’ Prisons may be Illegal, but they still Exist in Texas and Washington (by Noel Brinkerhoff, AllGov)

ACLU Sues Biloxi, Mississippi, over Debtors’ Prison (by Steve Straehley, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Musk and Trump Fire Members of Congress

- Trump Calls for Violent Street Demonstrations Against Himself

- Trump Changes Name of Republican Party

- The 2024 Election By the Numbers

- Bashar al-Assad—The Fall of a Rabid AntiSemite

Comments