Clinton-Appointed Judge Supports Gag Orders on FBI National Security Letter Recipients

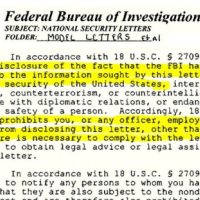

Portion of an FBI national security letter (graphic: FBI.gov)

Portion of an FBI national security letter (graphic: FBI.gov)

By Elizabeth Warmerdam, Courthouse News Service

(CN) — In a decision unsealed this week, a federal judge ruled that so-called national security letters issued by the government to gain subscriber information from banks, telecommunication companies, Internet service providers and others are not unconstitutional.

U.S. District Judge Susan Illston's ruling (pdf) means that the government can continue to issue the letters known as NSLs with accompanying gag orders that forbid the recipients to disclose the letters to the public or to the target of the subpoenas.

Federal investigators issue thousands of these letters each year to Internet service providers, insurance companies, doctors, banks and other institutions every year. The letters, which seek personal information about the companies' customers, do not require a judge's signature.

In order to constitutionally impose a prior restraint, the government must ensure that numerous safeguards apply, including the opportunity for a prompt judicial review and a demonstration that a gag order is necessary.

In a 2013 ruling, Illston found the letters facially unconstitutional because the NSL statute allowed the government to impose indefinite gags in every case, with no obligation for judicial review. The statute also limited the court's ability to weigh the necessity of the NSLs.

At the time, Illston ordered the government to stop issuing the letters, but she stayed her ruling pending a Ninth Circuit appeal.

While the case was on appeal, Congress amended the NSL statute through the passage of the USA Freedom Act of 2015, leading the Ninth Circuit to remand the case to Illston to reexamine the constitutionality of the letters in light of the changes to the law.

Among the changes, the government is now required to provide the NSL recipient with notice of the right to judicial review as a condition of prohibiting the receipt of the letter. The amended statute also permits the government to modify or rescind a nondisclosure requirement after an NSL is issued.

If the recipient notifies the government that it objects to or wants a court to review the nondisclosure requirement, the government must apply for a nondisclosure order within 30 days. The court can set aside the government's request if it is found to be unreasonable or unlawful.

Additionally, in the event of a judicial review the government's application for a nondisclosure order must be accompanied by certification from a specified government official stating why the absence of a prohibition of disclosure would result in a danger to national security, interfere with a criminal investigation or put someone's life in danger.

Congress also eliminated the provision that precluded certain NSL recipients from challenging a nondisclosure requirement more than once per year.

The amendment to the law "cures the deficiencies previously identified by this court," Illston said.

In addition to the changes to the law, the U.S. Attorney General adopted certain termination procedures for NSLs, the judge pointed out.

"The procedures require the FBI to re-review the need for the nondisclosure requirement of an NSL three years after the initiation of a full investigation and at the closure of the investigation, and to terminate the nondisclosure requirement when the facts no longer support nondisclosure," Illston said.

The cases at issue in this ruling were brought by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which represents two service providers that challenged the NSLs on the grounds that the gag requirement illegally limited their rights of speech.

EFF staff attorney Andrew Crocker said that they are "extremely disappointed that the superficial changes in the NSL statutes were determined to be good enough to meet the requirements of the First Amendment."

"NSL recipients can still be gagged at the FBI's say-so, without any procedural protections, time limits or judicial oversight. This is a prior restraint on free speech, and it's unconstitutional," he said.

In a silver lining for the EFF, Illston ruled that the FBI had failed to provide sufficient justification for one EFF client's challenges to the NSLs.

Illston said that the government did not show "that there is a reasonable likelihood that disclosure of the information subject to the nondisclosure requirement would result in a danger to the national security of the United States, interference with a criminal, counterterrorism or counterintelligence investigation, interference with diplomatic relations or danger to a person's life or physical safety."

She prohibited the government from enforcing that gag order. However, EFF's client is still not allowed to identify itself because the court stayed that portion of the decision pending appeal.

EFF vowed to "take this fight to the appeals court, again, to combat USA Freedom's unconstitutional NSL provisions."

To Learn More:

Order Re: Renewed Petitions to Set Aside National Security Letters (U.S. District Court, Northern District of Columbia) (pdf)

National Security Letters (Electronic Frontier Foundation)

Two Email Companies Close Shop rather than Reveal User Details to Government (by Matt Bewig, AllGov)

Judge Rules National Security Letters Unconstitutional (by Matt Bewig, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Musk and Trump Fire Members of Congress

- Trump Calls for Violent Street Demonstrations Against Himself

- Trump Changes Name of Republican Party

- The 2024 Election By the Numbers

- Bashar al-Assad—The Fall of a Rabid AntiSemite

Comments