Chemical Safety Reforms Fall Victim to Political Roadblocks Engineered by U.S. Chemical Industry

(graphic: Getty Images)

(graphic: Getty Images)

By Mark Collette and Matt Dempsey, New York Times

The explosion that flattened much of the farming community of West, Texas, in 2013 was the equivalent of a magnitude 2.1 earthquake, killing 15, injuring more than 200 and prompting President Barack Obama to order a sweeping overhaul of chemical safety laws.

Obama, however, will leave office with little to show for his edict, having succumbed to the power of the American chemical industry.

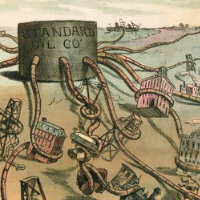

It extols its self-policing programs, raises terrorism fears to block the public's right to know and pours about $200 million into lobbying every year. The prevention of chemical disasters remains governed by a tattered patchwork of regulations administered by agencies that have neither the staff nor political support to enforce or improve upon them. And the public has been left largely in the dark about what goes on at facilities that might endanger their lives.

The same day Obama issued his order, three months after the explosion, West's own congressman argued there was no need for reforms.

Rep. Bill Flores, R-Waco, said the problem stemmed from West Fertilizer's "failure to comply with existing regulations and the lack of oversight and enforcement. It didn't occur from a lack of regulations."

In fact, there were no regulations to prevent the explosion. The material that blew up wasn't part of the Environmental Protection Agency's Risk Management Program. It wasn't among the chemicals that trigger aggressive preventative measures under the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

The original fire at the plant was later determined to be an act of arson - but a federal chemical security program run by the Department of Homeland Security wasn't even aware of the West facility, because it hadn't voluntarily reported its explosive inventory.

The main problems, federal investigators found, were that the fertilizer was stored in wooden bins, too close to homes and schools, and too near tanks of other hazardous products. And there were no regulations or inspectors that forced the company to do otherwise.

A year and a half later, another chemical disaster struck. This time, a gas leak killed four workers at a DuPont plant outside Houston.

The company had a troubling pattern of injuries and fatalities around the country in the last decade. A Houston Chronicle investigation in early 2015 exposed problems at the La Porte pesticide plant, including broken ventilation fans, missing or inadequate gas masks and alarms, and equipment in disrepair, all later confirmed by the U.S. Chemical Safety Board.

That agency, which can issue recommendations but cannot penalize companies, found that the company failed to do a hazard analysis before using a faulty procedure to unclog pipes, ultimately leading to the release of about 23,000 pounds of toxic methyl mercaptan.

The failure violated OSHA standards and underscored glaring gaps in chemical regulation, just like in West.

But no member of Houston's legislative delegation attempted a solution. Since 2001, only Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Houston, has pushed a chemical safety bill. It would have allowed the government to dictate security measures to protect against terrorism. She introduced versions of it five times, but none made it out of committee.

Republicans Ted Poe, John Culberson, Kevin Brady and Randy Weber - and Democrat Gene Green, whose district encompasses some of Houston's heaviest industrial areas - count the petrochemical industry among their biggest campaign contributors, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics. Those benefactors include Valero, Exxon Mobil and Halliburton.

No one in the local delegation would agree to an interview with the Chronicle to discuss his or her track record on chemical safety.

Companies like Chevron and Koch Industries, since 2009, have been the biggest sector contributing to Flores' campaigns, giving more than $1.1 million. One in 5 dollars came from petrochemicals.

In a recent email, Flores said again that "insufficient oversight" factored into the extent of the West explosion and that he was hopeful that the new administration can "improve oversight and processes that have been deficient."

Insufficient oversight is undoubtedly a problem - partly created by budget cutting in Congress. The EPA commits less than 1 percent of its dwindling budget to chemical safety. OSHA has only 267 inspectors for about 15,000 chemical facilities. The Chemical Safety Board now has just 50 employees and responds to just 34 percent of fatal accidents - though, under new leadership, it is trying to deploy to more.

President-elect Donald Trump has said he would like to gut the EPA. He has said less about OSHA, but his pick for labor secretary, fast-food executive Andrew Puzder, was described by AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka as "a man whose business record is defined by fighting against working people."

OSHA tried to react to West in July 2015 with what seemed a simple fix. Until then, large fertilizer depots were lumped in with small-time retailers like gas stations. By changing its interpretation of "retailers," OSHA could make companies like West Fertilizer follow complex safety rules like refineries and chemical plants.

"The industry ran up to Capitol Hill," said Debbie Berkowitz, a former senior OSHA official now with the National Employment Law Project. "Now there's a rider on an appropriations bill that says OSHA can't enforce this."

The rider was only temporary, and the fertilizer industry wanted a long-term fix. So it turned to the courts.

The Agricultural Retailers Association and The Fertilizer Institute pitted six attorneys against the Labor Department's three, arguing that the revised retailer definition constituted a new rule, and that OSHA should therefore follow the usual process: post notices, accept thousands of comments, convene special panels to study the effects on small businesses, weigh costs and benefits, and, after all that, face a potentially obstructive review by the White House regulatory czar.

OSHA and labor groups noted in their court filings that the industry hadn't objected years ago when the agency first interpreted the retail rule to exclude their plants, without the long rule-making process.

But the federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., agreed with the industry. OSHA is appealing, and the legal fight itself promises to bog down the effort to cover fertilizer plants for years, if not indefinitely.

Several months before that court ruling, 41 members of Congress penned a letter to the House Appropriations subcommittee that deals with OSHA, urging it to scrap the new retailer definition.

The letter didn't mention the West explosion.

Flores, West's congressman, was one of those who signed it.

Obama's order was a virtual blank check to the EPA and OSHA to do what he, as a senator, had championed: require safer alternatives to explosive and toxic chemicals, and expand the reach of federal programs that oversee safety at plants and refineries.

But just months after OSHA posted its retail memo, the chemical industry's leading trade association published a white paper extolling its nearly 30-year-old voluntary safety initiative, Responsible Care. The American Chemistry Council program provides the public and the government with some statistics but no details about the causes of accidents, and it prescribes no specific safety measures or sanctions.

The EPA took the message to heart. So did bureaucrats at a powerful but lesser-known office: Information and Regulatory Affairs. They met twice as much with industry lobbyists as they did with public interest groups, White House records show. Lobbyists from Exxon Mobil, Honeywell, Tesoro and Arkema were among those in the meetings.

The result: an EPA proposal that requires companies to study chemical alternatives and do safety audits but ultimately leaves it up to them to decide what course to take. It follows industry assertions that steps like adding chemicals to the list of regulated substances or reaching beyond the 4 percent of facilities now inspected under the Risk Management Program, are too complicated.

Most surprisingly, the new rule doesn't apply to facilities with ammonium nitrate, the chemical that blew up in West.

The new requirements for private audits by outside companies and for companies to more deeply analyze safety failures and near-misses don't require companies to reveal findings to the public. In any case, the new rule could be entirely rejected by the incoming administration.

"When the EPA makes a judgment, they have everyone around the table," said Rena Steinzor, a University of Maryland law professor who tracks chemical regulations. "The oncologists, epidemiologists, statisticians, geologists, climatologists - everybody who needs to be there to make a judgment about how best to solve a problem threatening public health. Then you go over to (Information and Regulatory Affairs), and it's as if they pull a lever, and everybody drops to the basement except the economists."

That agency, part of the executive branch, gets final say over new regulations. It calculates the price of plant upgrades but gives little consideration to less quantifiable benefits, like not killing workers and neighbors, said Eric Frumin, a longtime labor activist with Change to Win. Even under Obama, it has hawkishly adhered to the conservative philosophy that cost trumps other considerations.

The agency gives industry great access in what Steinzor calls its "all-you-can-meet" policy - meeting five times more often with corporate representatives than advocates over one decade she studied.

It's no wonder, she said, that the proposed risk management rule looks so much like Responsible Care.

"You can adopt Responsible Care and end up with a whole bunch of paperwork on how everybody has to be safe," Steinzor said. "The (BP) Texas City plant had that (when it blew up in 2005, killing 15 workers). It's all in a file drawer. It's a paper tiger."

The chemistry council says Responsible Care has helped reduce worker injuries to put the industry's rate among the lowest of any manufacturing sector.

Mike Walls, head of regulatory affairs at the council, said the government should better enforce existing laws, while programs like Responsible Care constantly look to identify areas of improvements.

The town of West is on the mend, and DuPont is preparing for a $60 billion merger with Dow Chemical Co. that will make it one of the three largest agrochemical companies in the world. It's decommissioning the La Porte site.

But the broader lessons of West and DuPont have yet to sink in.

Even though DuPont released a summary of its own investigation into the accident, largely pointing to errors by employees, it still hasn't given a full accounting of what happened.

The Chemical Safety Board has yet to issue a final report, though it doesn't expect its findings to differ greatly from an interim report released in 2015. It showed that the entire La Porte pesticide building posed a threat to workers and to public safety.

Families of some of the dead workers at La Porte reached confidential settlements with DuPont; other lawsuits are in progress.

While government stalls, DuPont and the American Chemistry Council continue to assure the public and lawmakers that risk is well under control.

Plants repeat that message after nearly every release big and small along the Houston Ship Channel, up the Texas City shoreline, along the New Jersey Turnpike and everywhere else that the industry has to explain its mishaps in late-night phone messages and email blasts: There is no cause for alarm. People are not in danger.

Since West, at least 46 have died in U.S. chemical plants.

Susan Carroll contributed to this story.

To Learn More:

Chemical Industry Self-Policing Called into Question, Government Oversight Lax (by Steve Straehley, AllGov)

Chemical Industry and Republican Lawmakers Succeed in Stalling EPA Chemical Regulation Process (by Steve Straehley, AllGov)

EPA Allowed Chemical Industry to Control Panel Assessing Cancer Danger in Drinking Water (by Noel Brinkerhoff and Danny Biederman, AllGov)

“Chemicals of Concern” List Still on Hold after 21 Months of Chemical Industry Lobbying (by Matt Bewig, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Musk and Trump Fire Members of Congress

- Trump Calls for Violent Street Demonstrations Against Himself

- Trump Changes Name of Republican Party

- The 2024 Election By the Numbers

- Bashar al-Assad—The Fall of a Rabid AntiSemite

Comments