Dictator of the Month: Ali Khamenei of Iran

Friday, November 25, 2011

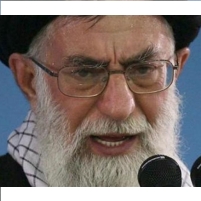

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

To hear some commentators, you would think that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the president of Iran, was the most dangerous man in the world. In reality, he has almost no power whatsoever. He does not control Iran’s nuclear program. He does not control Iran’s military. If the Iranian parliament passes a bill and Ahmadinejad signs it, it does not become law because it can still be vetoed by the real powers-that-be…the Guardian Council of religious leaders and the head of the Guardian Council, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Pundits who demonize Ahmadinejad are falling into a trap set by the true dictators of Iran, who use him as a lightning rod to divert attention away from themselves.

In my book Tyrants: The World's 20 Worst Living Dictators, I included a chapter about Khamenei, which I reprint below. Those who are only interested in the period when Americans entered the scene can scroll down to the paragraph before the heading “THE SHAH.” For those who are only interested in Iran’s current leadership, you can scroll down to the heading “THE MAN.” However, Iran has a rich and fascinating history, and learning about this history makes it easier to understand how Iran reached its current position at odds with the Western world and ruled by a theocracy that does not enjoy the support of the majority of the population.

THE NATION—Strategically located with borders on the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean and seven nations, Iran is one of the only countries in the world with an extensive history of both invading other countries and being invaded and occupied by foreign powers. It was the first Middle Eastern nation in which commercial quantities of oil were discovered (1908); the first in the region to have a revolution demanding a constitution (1905-1911); the first to have a parliament and the first to have a multiparty system (1941). It was also the first nation in the world to be the victim of a CIA-sponsored coup (1953) and the first Islamic nation to have a mass revolution in which millions of people took part (1979).

Until the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in neighboring Iraq, Iran was also the only country in which the government was controlled by followers of Shi’a Islam. Although estimates vary, almost 90% of the population of more than 70 million are Shiites. There is a substantial Sunni population, most of whom are members of ethnic minorities, in particular Arabs and Kurds. The Shi’a have a long history of oppression. They inhabit areas under which are found the world’s most important reserves of oil, yet they have rarely benefited from what should have been their good fortune. In both Iraq and Bahrain, where Shiites are the majority, and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, where they are the minority, the oil wealth has been exploited by Sunnis.

For most of its history, the people of the nation have referred to their country as Iran, while Europeans called it Persia. In 1935, the government asked foreigners to start using the term Iran, and gradually Iran replaced Persia in common usage, although the old name has lingered in certain cases, such as “Persian Gulf” and “Persian rug.”

EARLY HISTORY—Settlements in what is now Iran date back to at least 8,000 BC, and Iran has its own monotheistic religion, Zoroastrianism, which was founded in about 1,000 BC. The first and probably greatest Persian dynasty was that of the Achaemenians, which lasted from 640 BC to 323 BC. In 550 BC, Cyrus the Great created an empire that stretched from Egypt and the Aegean Sea to the Oxus River, which divides Russia and Afghanistan. Cyrus is credited in the Bible with freeing the Jews from captivity and allowing their return to Jerusalem.

Darius the Great, who reigned from 522 BC until 486 BC, earned recognition as the most famous Persian king because he invaded both Scythia (southern Russia) and Greece, where his army was finally defeated at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Darius also ordered the construction of a 1,600-mile Royal Road that postmen could cover in six to nine days, and a canal that connected the Nile River with the Red Sea. He built the Persepolis Palace, oversaw the creation of a banking system and established an early system of coinage.

In 334 BC, Alexander the Great defeated the Persian army and destroyed Persepolis. Alexander died two years later. One of his generals, Seleucus, stayed on and founded the Seleucid dynasty. The Parthians came down from the steppes in the northeast, defeated the Greek Seleucids and gained control of Persia and Mesopotamia. The Parthians would rule the area for 471 years. In 53 BC, they defeated the Roman army under Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae. Seventeen years later, they fought back an attempted invasion by Mark Anthony. In AD 116, Trajan became the first Roman emperor to reach the Persian Gulf, but even he was eventually forced back by the Parthians. The Parthian dynasty finally fell in 224, not to an invading force, but to a national uprising led by Ardeshir I. The Sassanians, a purely Persian dynasty, ruled from 224 until 642, during which time they revived Persian culture and Zoroastrianism. Among the most noteworthy Sassanian leaders was Khosrow I, who oversaw a cultural renaissance and whose chancellor, Bozorgmehr, is credited with creating the precursor of the modern game of backgammon. Between 629 and 632, the dynasty was ruled by two female monarchs, one of whom, Purandokht, signed a peace treaty with the Byzantines.

The seventh century would prove critical to Persian history. In 632, Muhammad, the founder of Islam, died. The next year, his Arab followers began to spread their faith through conquest, moving through present-day Kuwait to Mesopotamia. The last Sassanian king, Yezdigird III, rejected Islam, calling the Arabs lizard-eaters and baby-killers. In 642, the Arabs defeated the Persians at the Battle of Nihavend, ending more than four centuries of Sassanian rule. Many Persians welcomed Islam because it taught equality and unity and was a relief from the feudalism of Zoroastrianism. In 661, the assassination of Muhammad’s son-in-law, Imam Ali, led to a schism in Islam between the Sunnis and the Shiites. The Shiites believed in the divine right of the family of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and her husband Ali, and claimed that only someone who was a direct descendant of this couple could be fit to rule. Unlike the Sunnis, they also believed that Shiite leaders were infallible; a belief that still has a strong influence on Iranian life—and government—more than 1,300 years later. During a later dynasty, that of the Abbasids, three branches of Shi’a Islam developed. One of the branches, the Jaafaris (also known as Twelvers), has reigned in Iran ever since.

The Shi’a rejected as usurpers the Umayyad Caliphate that ruled the Islamic world between 661 and 750 and were glad to join the Abbasids in defeating the Umayyads. The Abbasid Caliphate, lasting from 750 until 1258, marked the pinnacle of Islamic power, and Iranians contributed greatly in the fields of science, medicine, and the arts. By shifting the capital of the caliphate from Damascus to Baghdad, the Abbasids brought about a cross-pollination of Semitic and Persian cultures. In the 13th century, Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, a prince of Khiva, swept south and conquered Persia. In 1219 one of his governors murdered the members of a 500-man trade mission from the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, who then sent a delegation to demand an apology and compensation. Ala ad-Din Muhammad had the leaders of the delegation beheaded. Genghis Khan responded by sending a 200,000-man army to destroy Ala ad-Din Muhammad and all his lands, which they did in brutal fashion. In the 1250s, Genghis Khan’s grandson, Hulagu Khan, sacked Baghdad and executed the caliph, putting an end to the long-declining Abbasid Caliphate.

In the early 16th century, Shah Ismail I united Persia under a native leader for the first time in more than 800 years. Shah Ismail came from an important religious family. Although they were Sufis, they taught him Shi’a Islam. When he gained power, Ismail ordered Shiism to be the state religion and he went to great lengths to convert the Sunnis in his domain. Another leader of the Safavid dynasty, Shah Abbas the Great, defeated the Ottoman Turks and expanded his empire from the Tigris River to the Indus River. He was a brutal tyrant, but he was a skillful administrator and he made his capital, Isfahan, a center of art and architecture. In 1722, an Afghan chieftain, Mahmoud Khan, in bloody fashion, captured Isfahan and overthrew the Safavid dynasty. General Nadir Kuli expelled the Afghans and reinstated the Safavids, proclaiming himself shah, or king, in 1736.

By this time, Iran was attracting the attention of the Europeans, and the rivalry between Great Britain and Russia actually helped preserve Persia’s independence. In 1787, Aga Mohammad Khan proclaimed himself shah and by 1794 he had united Persia, beginning the Qajar dynasty that would last until 1925.

The Qajars signed treaties with the British, the Turks, and the Russians and conceded a good deal of territory, while modernizing Persia. Naser o-Din Shah also began granting commercial concessions to the British, beginning with a thirteen-year telegraph system project begun in 1859. Discontent with the shah’s selling of the country to a foreign power peaked when he gave the British the tobacco concession in 1890, and he was forced to rescind the concession two years later. By 1905, Persians fed up with government corruption organized a general strike and demanded a constitution. On August 5, 1906, Mozafar o-Din Shah decreed the creation of a constitution and an elected parliament, the Majlis. The writing of the constitution was dominated by secularists, but the clergy ensured that Twelver Shiism was declared the state religion and that only Jaafari Shi’a could serve as shah, government ministers, and judges. The radical clergy took the position that sovereignty does not rest with the people because Allah delegated it to the mujtahids, religious scholars and leaders. A century later, it is this position that continues to limit the acceptance of democracy in Iran.

REZA SHAH—On February 21, 1921, Reza Khan, a common soldier who rose through the ranks to become a brigadier general, in secret collusion with the British, led a bloodless coup at the head of an army of 1,200 men. Reza Khan banned gambling and alcohol and made himself popular by reducing the price of bread. In 1925 he proclaimed himself Reza Shah Pahlavi, beginning the short-lived but ambitious Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah set out to curtail the power of the clergy. He limited the jurisdiction of the religious Shari’a courts, and the state took over many religious schools. In 1928 he pushed through the Uniformity of Dress Law that forced men to dress in Western clothes with round peaked caps. Only clerics and theological students were exempted. In 1934 he visited Turkey and was impressed by that country’s modern ways. When he returned to Iran, he outlawed the wearing of veils by women and opened up to women all public places, including workplaces and schools. As for the men, he ordered them to replace their caps with European felt hats.

In 1935 he formally asked the governments of the rest of the world to stop calling his nation Persia, a name chosen by the Europeans, and instead call it Iran, the name traditionally used by the Iranians themselves. Domestically, Reza Shah took away the power of the Majlis and eliminated free speech. An admirer of Hitler’s nationalism, he invited German businessmen into Iran. Nevertheless, when World War II broke out, he tried to declare Iran neutral. However, the Allies were not interested in his position. They wanted to use the Trans-Iranian railway to move military supplies to the Soviet Union, so British and Soviet forces occupied the country in 1941. Reza Shah abdicated in favor of his twenty-one-year-old son, Mohammad Reza Shah, and he died in exile in South Africa in July 1944. Mohammad Reza would grow up to be a major player on the world scene and was commonly known internationally as The Shah.

THE SHAH—Mohammad Reza Shah was young, and it was difficult for him to assert power. The clergy tried to regain the power they had lost under Reza Shah, for example, by ordering women to wear veils while shopping. Still, when the war ended, the new shah did try to win support, in particular by annulling his father’s ban on Iranians going to Mecca on the hajj. He blamed the British for his father’s overthrow and he hated the Communists in the Soviet Union, so he moved his country closer to the United States.

NATIONALIZATION AND THE CIA—By 1950, Iranians were once again upset by the influence of foreign powers in their country and in particular the control of their oil industry by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The Shah appointed General Ali Razmara prime minister in June 1950. Razmara opposed the growing movement to nationalize the Iranian oil industry and was assassinated on March 7, 1951. Eight days later, the Majlis voted to nationalize Anglo-Iranian. On April 28, the Majlis elected Mohammad Mossadeq prime minister. Mossadeq tried to negotiate with the British, but in the end he enforced the Oil Nationalization Act and seized Anglo-Iranian’s assets. The Shah had no choice but to go along with what was clearly the will of the people. The British were furious and blockaded the Persian Gulf and prevented oil from leaving Iran. This caused the Iranian economy to collapse, but Mossadeq remained popular and the Shah was forced to give him increased powers.

In 1953, the CIA launched Operation Ajax to remove Mossadeq from power. Through infiltration, they tried to drive a wedge between Mossadeq’s secular and religious supporters. The Shah dismissed Mossadeq, but Mossadeq refused to give up his post, and the Shah and his wife fled to Rome. Fighting broke out between pro- and anti-Shah forces. Funded by the CIA and MI6, the conflict climaxed with a nine-hour battle in front of Mossadeq’s house that left more than 300 dead. Mossadeq was arrested and spent the remaining thirteen years of his life in prison and house arrest. General Fazlollah Zahedi declared martial law, the Shah returned to Tehran after less than a week away, and oil began to flow again.

The Shah became a really good friend of the United States, to whom he was beholden for his position of power. Between 1953 and 1960, the U.S. poured more than a billion dollars of aid into Iran, and thousands of Americans began working there, particularly in the oil industry. In 1964, the U.S. gave Iran a $200 million loan in exchange for the granting of diplomatic immunity for all Americans in the country. The Majlis passed this highly controversial move in a close vote. The Shah agreed to join the Baghdad Pact with Turkey, Iraq, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom, and in exchange he was given the role of policeman of the Gulf. Between 1953 and 1969, the U.S. would give the Shah as much money in military grants as it gave all the other countries of the world combined. In 1960, the Shah returned the favor by donating millions of dollars to Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign.

On January 6, 1963, the Shah instituted a White Revolution that allowed women to vote, promoted literacy, nationalized the forests, encouraged profit-sharing in industry and ordered agrarian reform in which farmland was seized from landlords and taken over by the government. Having smashed his secular opposition, the Shah took aim at the radical clerics and, especially, the most popular of the clerics, Ayatollah Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini.

AYATOLLAH KHOMEINI—Born Ruhollah Mousavi in either 1900 or 1902, he was only five months old when his father was murdered on orders of the local landlord. He began religious instruction at the age of six. After finishing his secular education at fifteen, his brother tutored him in Islamic studies for four years. He attended a seminary in Arak and then moved to the religious center of Qom. He graduated theological school in 1925 with a degree in Shari’a, ethics, and spiritual philosophy and became a teacher of ethics and philosophy. Khomeini’s first book, The Secrets Revealed, which he published anonymously in 1942, attacked secularism while upholding private enterprise. In 1945, he graduated to the rank of hojatalislam, a step below ayatollah, which gave him the right to gather disciples. During the early 1950s, Khomeini was critical of Mossadeq because he considered him to be overly influenced by the communist Tudeh Party, a view he shared with the Americans. But he was also critical of the Shah for his “plundering of the nation’s wealth” by making deals with the U. S. government and with the Western oil companies, and he denounced the Shah’s White Revolution.

On March 22, 1963, following a protest by theological students over the opening of liquor stores, paratroopers raided the school where Khomeini taught and killed several students. On June 3, Khomeini gave a major speech denouncing the Shah, and two days later he was arrested. This led to large-scale rioting and the imposition of martial law. Officially, government troops shot eighty-six people to death, although the true figure was probably much higher. After two months in jail, Khomeini was transferred to house arrest. Released on April 6, 1964, he immediately resumed his anti-Shah speeches. On November 4, he was arrested again, but this time the Shah kicked him out of the country. Khomeini went first to Turkey, but then settled in rather comfortably in Najaf, a Shiite holy city in Iraq.

In 1967, the Shah imposed the Family Protection Law, which gave women the right to divorce without their husband’s permission and required husbands to obtain their wife’s permission before marrying a second wife. It also transferred family affairs from the Shari’a courts to secular courts.

The Shah signed a border treaty with Iraq in March 1971 that also gave Iran the right to send 130,000 pilgrims a year to visit Shi’a holy sites in the Iraqi cities of Karbala and Najaf. This part of the treaty had the secondary effect of giving Khomeini’s followers the opportunity to visit him and to bring back to Iran tapes of his speeches.

By 1972, the year that President Nixon visited him in Iran, the Shah was becoming increasingly autocratic and megalomaniacal. He had taken over the appointment of government clergy, and his National Security and Intelligence Organization (SAVAK), which was trained by the CIA, the FBI, and Mossad, was operating as a brutal political police force. Interviews showed that 90% of SAVAK prisoners were beaten, 80% were whipped, and a majority were burned with cigarettes. In August 1973, the Shah declared, “My visions are miracles that saved my country. My reign saved my country, and it had done so because God is on my side.” In March 1975, he dissolved the multiparty system and created a single political party, his own. That same year, Amnesty International announced that Iran had the highest death penalty rate in the world. In 1976, the Shah boasted in an interview that he had 100 paid informers working inside the United States keeping an eye on the 60,000 Iranian students who were studying there.

On November 15, 1977, the Shah visited President Jimmy Carter at the White House. His visit was met with large protests by Iranian students. Back in Tehran, more than 10,000 students marched in support of the students in the U.S. One student was killed and many were arrested. When the arrested students were released on the authority of a civilian court, the growing Iranian opposition took heart that they were now less likely to be subjected to SAVAK torture. Opposition to the Shah was spreading to diverse sections of the population. In addition to the student movement, the bazaaris, the traditional merchants, had turned against the Shah because of his harsh campaign against profiteering. But it was the clerics who were leading the opposition. On October 7, 1977, masked religious students at Tehran University demanded that male and female students be segregated outside the classroom and handed out pamphlets to young women that said, “If you violate these guidelines, your lives will…not be safe.”

In January 1978, the government published an article that accused Ayatollah Khomeini of being (1) involved with international communists, (2) a tool of colonialists, (3) of foreign origin, (4) of having worked as a British spy, (5) of having homosexual tendencies, and (6) of writing erotic poetry. This tactic of character assassination backfired. In Qom, the seminaries and the bazaars shut down in protest. Security forces shot to death seventy protesters, which led to the uniting of the opposition despite their deep philosophical differences. For the first time, street protests were accompanied by chants of “Death to the Shah,” and some police changed into civilian clothing rather than follow orders to shoot the protestors.

It finally dawned on the Shah that he was facing a major problem. In an attempt to appease the opposition, he increased the quota of pilgrims to go to Mecca; he banned pornographic films; he released the merchants who were in prison for overcharging; and he fired the head of SAVAK. But his efforts were undercut when media reports of Kermit Roosevelt’s insider account of the CIA’s role in the overthrow of Mohammad Mossadeq and the restoration of the Shah reached Iran. From Iraq, Khomeini told his followers to keep protesting until the Shah himself was overthrown.

On August 19, 1978, a fire broke out in the Rex Cinema in the oil port city of Abadan. The emergency doors were locked and 410 people died. Most of the public blamed SAVAK, and this event raised anti-Shah emotions to a higher level. The clergy issued a list of fourteen demands that included banning cinemas and casinos, releasing Islamic political prisoners, and allowing Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran. The Shah ordered the release of jailed clerics, closed the casinos, lifted censorship and increased the pay of government employees and members of the military. But the protests continued, and on September 7 the Shah imposed martial law. On September 18, employees of the Central Bank of Iran released documents that showed that members of the ruling elite were transferring their savings abroad.

On October 6, the Iraqi government, which was ruled by Sunnis and was worried that the events in Iran would spread to the majority Shiites in Iraq, expelled Khomeini, who continued his exile in Paris. From there, he urged the Iranian people to withhold payment of taxes and reminded his followers that it was the duty of the faithful to die if necessary in the fight against the Shah. However he also stated that he opposed armed struggle because it led to a chain of revenge. On December 7, President Carter said that although he supported the Shah, it was up to the Iranian people to choose their own government. To the Iranians, this was a signal that the United States no longer supported the Shah. If fact, the Carter administration had already made contact with Khomeini, who promised to continue the flow of oil if the U.S. would help get rid of the Shah.

THE REVOLUTION SUCCEEDS—In January 1979, newspapers in Iran began running large pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini. On January 13, Khomeini established a Council of the Islamic Revolution to form a provisional government and convene a constituent assembly to write a new constitution for an Islamic Republic. He also ordered the Council to negotiate directly with the military in order to avoid bloodshed. Three days later, the Shah left Iran, although he did not formally abdicate. Still, there were celebrations in the street and people toppled statues of the Shah and his father, and they cut the Shah’s picture out of the center of paper money.

On February 1, Ayatollah Khomeini arrived in Tehran after fourteen years in exile. He was at least seventy-six years old. In the military, senior officers supported the Shah, middle-rank officers supported the revolution, and the rank and file were mixed. However, only the 30,000-strong Imperial Guards actually resisted. The revolutionaries captured the government television station, the Majlis building, and the military academy and overran the military bases. On February 11, the armed forces, down from 300,000 to 100,000 because of desertions, declared its neutrality, while the air force and armed civilians fought the Imperial Guards.

The Shah was so unpopular that the opposition covered a wide range of movements and ideologies. There were Communists, radical students, mainstream social democrats, groups that promoted a fusion of Islam and Marxism, traditional Muslims, ethnic minorities, and Islamic extremists. But only Khomeini and his supporters were well-financed. Khomeini received help from Muammar al-Gaddafi, the dictator of Libya, and from the Palestine Liberation Organization. But of more value to him, he was supported by the bazaaris, the traditional merchant class that the Shah had attacked. Within weeks the national army, now fully supportive of Khomeini, was fighting the Kurds in the north. On March 22, anti-Khomeini Islamic extremists assassinated Khomeini’s first chief of staff.

Khomeini immediately set to work reshaping Iranian society and creating an Islamic Republic. Democracy, he said, “is a Western idea. We respect Western civilization, but will not follow it.” He and his supporters argued that the centralization of power in the hands of a single man was not a form of dictatorship because he would rule according to divine will, not his own. Those who opposed the political leadership of the ulema, the leading clergy, were enemies of the Revolution.

He created a system with an elected president who would serve a four-year term. The president would be responsible for signing and executing laws passed by the Majlis. All this seemed to fall within the parameters of a typically representative government. But Khomeini added a new element: the twelve-man Council of Guardians. Six of the Council members would be members of the clergy appointed by the Rahbar, the Leader (Khomeini), and the other six would be jurists appointed by the head of the judicial branch who was also appointed by the Leader. The Guardian Council would be allowed to exercise veto power over laws passed by the Majlis and approved by the president. Because the vast majority of Iranians were pleased to have Khomeini as their leader, this structure did not at first attract much attention.

Khomeini banned co-education and required female government employees to wear veils. When women protested this decree in the streets, men threw stones at them. However, Khomeini responded to the women’s position and allowed them to remain unveiled—for the time being. He promised freedom of the press—except for views deemed “detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights of the public.” As for political parties, they were “a fatal poison” and their leaders “soldiers of Satan.” There was no need for such institutions because Allah would guarantee the national well-being. To be on the safe side, Khomeini banned political demonstrations of the sort that had brought him to power. On July 2, disaffected revolutionaries wrote a letter to Khomeini criticizing him for burning books, firing teachers, and controlling the media. They accused him of changing the slogan “unity of work [Iranians speaking with one voice] to “unity of following my words.”

THE HOSTAGE CRISIS—On October 22, President Carter allowed the Shah, who was dying of cancer, to enter the United States for medical treatment. This was the perfect excuse for Khomeini and his supporters to brush aside all dissent and rally the masses once again. On November 1, three million people marched in Tehran demanding that the U.S. extradite the Shah to Iran. Three days later, with Khomeini’s tacit approval, 450 militant students attacked the U. S. embassy and took over the building after a three-hour struggle. They were looking for documents that demonstrated U.S. support for the Shah. American officials managed to shred many documents, but the students would later painstakingly piece them back together. The Iranian cabinet, which was more moderate than Khomeini, resigned in protest. Besides the documents and the building itself, the students also captured ninety people inside the building, including sixty-three Americans. They announced that they would release these hostages if President Carter would extradite the Shah. Carter refused.

Eventually, the students whittled the hostages down to fifty-one men and two women. One hostage was released several months later for health reasons, but the rest were held captive for 444 days. On July 27, 1980, the Shah died in Egypt, removing the original reason the hostages had been taken. However, they were not released until the day that Carter left office and was replaced as president by Ronald Reagan, who, a few years later, would have his own embarrassing problems with the Iranians.

In June 1981, it was revealed that some of those documents pieced together by the students showed that Abol Hassan Bani-Sadr, who had been president of Iran since February 4, 1980, had met secretly with the CIA. Khomeini removed him from office and he fled to Paris.

THE CRACKDOWN—Meanwhile, Khomeini continued his attempts to impose his interpretation of Islam on the Iranian people. He banned chess, considering it a form of gambling. He banned the playing of music in public and shut down 420 movie theaters. He nationalized all banks and 450 major industrial businesses, and he made foreign trade a government monopoly. He closed the universities and did not reopen them until they had been purged and Islamicized. He ordered all female government employees to wear the chador. Tens of thousands of komiteh, revolutionary guards, were sent out to police the streets and enforce cultural restrictions, and citizens were urged to spy on and report on their neighbors and relatives. In December 1981, special judges were assigned to combat “impious acts,” including homosexuality, adultery, gambling, and the catch-all, hypocrisy, not to mention showing sympathy for hypocrites and atheists. The death penalty was applied to a range of crimes, including rape, prostitution and drug trafficking. As Khomeini put it on September 9, 1981, “When the Prophet Muhammad failed to improve the people with advice, he hit them on the head with a sword until he made them into human beings.” In the three months following the dismissal of Bani-Sadr, 1,000 Iranians were executed, including at least 182 on September 18 and 19 alone. According to estimates by Amnesty International, during the first five years of Khomeini’s reign 5,000 Iranians were executed.

Many of Khomeini’s policies were widely approved. For example, he raised the minimum wage and outlawed interest-bearing loans. In 1982 he also began to make concessions, declaring an amnesty for 10,000 political prisoners, ending his campaign against music and allowing non-Muslims to consume alcohol.

THE IRAN-IRAQ WAR—Across the border in Iraq, that nation’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, viewed the developments in Iran as both a potential threat and a potential opportunity. As a Sunni who ruled a population that was mostly Shiite, he was not pleased that a Shiite government had been created next door, and especially so because it had come to power as the result of a mass revolution. The Iraqi Shiites considered Ayatollah Khomeini their hero, and Khomeini responded by urging them to overthrow Saddam and his secular Ba’athist Party. Saddam saw Iran as having been weakened by all the chaos, and if he could defeat Khomeini, he could expand his borders while at the same time crushing the Shiite hero. The Iranians also gave support to the anti-Ba’athist Kurds in the north of Iraq, while the Iraqis urged the Iranian Arabs in Khuzestan to sabotage oil installations and demand autonomy.

In June of 1979, Iraqi planes in pursuit of Kurdish nationalists bombed Iranian villages. The following month, only five months after the Ayatollah Khomeini’s return to Iran, Saddam Hussein took over as the official head of state in Iraq. He deported 15,000 Iraqi citizens of Iranian descent and began executing Shiites suspected of being sympathetic to the Iranian Revolution. The border between Iran and Iraq was not officially drawn until 1913, and a dispute continued over control of the Arvand-Roud (known in Iraq as the Shatt al-Arab), a river formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that discharges into the Persian Gulf. In September 1980, Saddam abrogated a 1975 border treaty and claimed Iraqi control of the Arvand-Roud. On September 21, Iranian artillery fired on Iraqi ships in the Arvand-Roud. The next day the Iraqis dropped bombs on nine Iranian air bases, while the Iranians bombed seven Iraqi cites, including Baghdad and Basra. On September 23, Saddam Hussein sent 33,000 Iraqi troops across the Iranian border along a 300-mile front. Saddam thought that the Sunni Arabs in Iranian Khuzestan would rally to his support, but he was wrong.

Both sides attacked each other’s oil refineries and Iraq was able to take control of the Iranian oil port of Khorramshahr. On October 9, Iraq used surface-to-surface missiles for the first time, killing 110 civilians in Dezful in Khuzestan. In December, Iraq invaded Iranian Kurdistan, this time successfully hooking up with Kurdish rebels who were already fighting against the Iranian government. The armies of Iran and Iraq fought primarily on Iranian soil, trading attacks and counterattacks with heavy loss of life. By the end of the first year of fighting, 38,000 Iranians had been killed, along with 22,000 Iraqis. On March 19, 1982, Iran launched a massive counterattack. In eight days the Iranians were able to push the Iraqis back twenty-four miles and recover 800 square miles. In the process, they took 15,450 prisoners. The following month they won back another 500 square miles. On May 24, 1982, Iran regained the now ruined city of Khorramshahr, sweeping up a third of Iraq’s forces as prisoners. Except for a few minor pieces, the Iranians had regained all of the land they had lost to the Iraqis in the first twenty months of the war. Khomeini twice rejected truce offers and, in his desperation to defeat Saddam Hussein, he quietly bought military equipment from Israel and sold oil to the United States. On July 13, the Iranian army made its first ground incursion into Iraq, but the attack failed and 10,000 Iranian soldiers were killed. In fact, the entire war bogged down, settling into a grim World War I-style stalemate. By the end of year three, 125,000 soldiers and civilians had lost their lives on behalf of a personal feud between Saddam Hussein and Ayatollah Khomeini.

In November 1982, the administration of U.S. president Ronald Reagan removed Iraq from the U.S. list of countries supporting terrorism (and put Iran onto the list) and restored diplomatic relations after an eighteen-year gap. Reagan began helping Saddam Hussein, beginning by turning over satellite photos of Iranian troops and then providing Saddam with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of agricultural credits that freed Iraq to spend its oil profits on its military. Much to the horror of the international community, Khomeini sent out human waves of 250,000 soldiers, many of them teenagers, leading to the deaths of 20,000 Iranians in one three-week period alone in early 1984. When Iran seized the Majnoon Islands in the marshes of southern Iraq, Iraqi troops stopped the Iranians with mustard gas and nerve gas.

On March 11, 1985, 60,000 Iranian soldiers tried to cross the Tigris River and attack Basra. Iraq repulsed the attack, but it took chemical weapons, 250 combat air sorties a day, and the elite Presidential Guard Division to do so. Iraq then retaliated by launching the War of the Cities, hitting Tehran with missile attacks. Iran bombed Baghdad. By the end of 1985, 200,000 Iranians had been killed and 45,000 had been the victims of chemical attacks.

If anything, the war only got uglier in 1986, culminating, on December 24, in Iran’s largest attack of the conflict, an attempt to take Basra. Over the next two months, 65,000 Iranian shells reduced the city to rubble, but they were unable to enter the city. Of the 200,000 Iranian soldiers who were part of the attack, 17,000 died and 45,000 were wounded.

RONALD REAGAN BLUNDERS INTO A BAD WAR—In November 1986, a Lebanese newspaper, Al Shira (The Sail) broke the news that while the Reagan administration had been supplying Iraq, it had also been selling weapons to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages held in Lebanon. In early 1987, Iraqi SCUD missiles killed 3,000 civilians in 35 Iranian cities and injured another 9,000. Iran responded by shooting more missiles at Baghdad. That same year, the United States agreed to provide protection to Kuwaiti oil tankers operating in the Persian Gulf, drawing American troops into the conflict in a more direct manner. On May 17, the Iraqis mistook the U.S. frigate Stark for an Iranian warship and hit it with two missiles, killing thirty-six American sailors. The Reagan administration forgave the Iraqis since the two countries were allies, but it was not so forgiving of the Iranians. On April 14, 1988, a U.S. frigate hit an Iranian land mine, wounding ten sailors. Four days later, the U.S. destroyed two Iranian oil platforms, sank a guided missile frigate, and knocked out an armed speedboat. It was the biggest American naval encounter since World War II. On July 3, the USS Vincennes, a $1.2 billion U.S. Navy guided missile cruiser, crossed into Iranian territory to chase a group of Iranian gunboats. In the midst of the exchange of fire, sailors on board the Vincennes spotted an Iranian airplane and shot it down. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a commercial passenger flight flying in its normal air corridor during a scheduled flight between Iran and Dubai. Two hundred ninety civilians from six nations were killed, including sixty-five children.

In March 1988, Iran made its last offensive against Iraq, attacking Kurdish areas in the north of the country. On March 16, the Iraqis, thinking the Kurdish town of Halabja was occupied by Iranian forces and Kurdish guerrillas, dropped poisonous gases on the town, killing thousands of Kurdish civilians. The Iraqis countered the Iranian offensive with a surprise attack on the Faw Peninsula in the south, in what would prove to be a decisive battle. On May 25, they cleared the approaches to Basra, thus recapturing almost all of the Iraqi territory that had been taken by Iran. Back in the north, in July, the Iraqis, along with a large force of anti-Khomeini Iranians, drove the exhausted Iranian army out of Iraqi Kurdistan. On the verge of defeat, the Iranian government agreed to a United Nations-sponsored ceasefire on August 20, 1988.

When the eight-year war was all over, the border between Iran and Iraq was unchanged, but there had been more than a million casualties. On the Iranian side, 262,000 people had lost their lives, including 11,000 civilians. Of those, an estimated 25,000 had been killed by gas attacks. Another 600,000 Iranians were wounded and 45,000 had been taken prisoner. Meanwhile, more than 105,000 Iraqis died, 400,000 were wounded and 70,000 were taken prisoner.

Even though the war was over, the killing in Iran continued. On July 24, 1988, the radical anti-Khomeini Mujahedin-e Khalq Organization (MKO) attacked Iran from Iraqi territory. They were easily repelled, but back in Tehran the government sought its revenge by executing 4,400 MKO members and sympathizers who were already in prison, including many who had been sentenced for nonviolent crimes such as distributing literature and collecting funds for the families of other prisoners. The man in charge of the executions at Tehran’s Evin Prison, Mustafa Pour-Muhammadi, was appointed Iran’s minister of the interior in 2005, a position he held for three years.

KHOMEINI PREPARES FOR THE POST-KHOMEINI PERIOD—As the Iran-Iraq War wound down, Ayatollah Khomeini, now well into his eighties, began to prepare Iran for life without him. Much to the surprise of many within his own regime, he softened many of his more repressive stances. In December 1987, for example, he refused to ban the showing of Western films on television even when they showed unveiled women, stating that they were religiously acceptable, and even sometimes educational…as long as they were not watched with lustful eyes. He also said that Shari’a law could be overruled if it was contrary to the interests of the nation or Islam. In August 1988 he legalized the selling of musical instruments (as long as they were used to play religious music) and even lifted the ban on chess. This outraged the conservatives who had always supported him. Khomeini countered their criticisms by telling them, “Based on your views, modern civilization must be annihilated and we must all go to live forever in caves and deserts.”

More important than these cultural changes were the revisions he instituted to the organization of the Iranian government. He established a 13-man Expediency Council to mediate the increasingly contentious disputes between the elected government and the Guardian Council. In April 1989, he created the Assembly for the Reappraisal of the Constitution which then eliminated the post of prime minister, increased the power of the president, and required the Leader to consult with the Expediency Council. Khomeini had been grooming a high-ranking cleric, Grand Ayatollah Montazeri, to take his place as Leader, but only five weeks before his death on June 3, 1989, Khomeini convinced the authors of the new constitution to lower the qualification requirements for the new Leader to make way for his new choice, a middle-ranked cleric named Ali Husseini Khamenei.

THE MAN—Ali Husseini Khamenei was born April 18, 1939, the second son of a religious family in the holy city of Mashhad in Khorasan Province. As a teenager, he was a disciple of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khatami, whose son, decades later, would be elected president of Iran. Khamenei studied in Najaf and then moved to Qom, where, in 1962, he became a student of Ayatollah Khomeini. When Khomeini was deported to Turkey, Khamenei returned to Mashhad and taught at a theological college. He was intensely involved in the movement to overthrow the Shah and was arrested six times, once spending two months in solitary confinement. In 1976 he went into internal exile, but returned to Mashhad when the revolutionary upsurge loosened the Shah’s grip on power. When Khomeini returned to Iran and established an Islamic Republic, Khamenei was one of his first appointments to the Islamic Revolutionary Council. He also served as Friday Prayer Leader of Tehran and he was one of Khomeini’s personal representatives on the Supreme Defense Council.

On June 27, 1980, Khamenei was giving a sermon at the Abudhar mosque in Tehran, when a bomb, presumably planted by the MKO, exploded, causing Khamenei injuries to his lungs and his arm and forcing him to spend several months in a hospital. This and another bombing eliminated other leaders, and in 1981 the Islamic Revolutionary Party chose him to be its candidate for president. Khamenei won with 95% of the vote. He also served in the Assembly of Experts that drafted a new constitution in 1982, and in 1985 he was reelected president. When Khomeini died, the Assembly of Experts, following his wishes, bypassed 200 ayatollahs and several grand ayatollahs and elected Khamenei Leader of the Revolution.

During the early years of his reign, Khamenei was not an aggressive leader and was satisfied to allow others to take charge of many of the responsibilities of governing.

RAFSANJANI—Like Khamenei, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was born into a religious family and studied in Qom, where he became a student of Ayatollah Khomeini. When Khomeini was deported, Rafsanjani handled Islamic charities on his behalf. Like Khamenei, he was active in the anti-Shah movement and was arrested and tortured by SAVAK. After the revolution, he was chosen to be the speaker of the Majlis, a position he held for nine years. In 1989, he was elected president of Iran and for the next several years he was the dominant force in Iranian politics. He improved relations with Europe, Japan, and the Soviet Union. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, Rafsanjani spoke out against the invasion, but when the United States led a coalition to oust Iraqi forces from Kuwait, he also opposed the presence of American troops in the region.

Known as the Commander of Constructiveness, Rafsanjani tried to make Islam relevant to young people by providing for them a better material life. He also urged Iranian expatriates to return to the country. In December 1991, the Guardian Council ruled that all candidates for the 1992 Majlis election must be approved by the Council, whereupon they disqualified all leftist candidates. Rafsanjani was reelected president in 1993, but with, by Iranian standards, a modest 63% of the vote. As Rafsanjani’s power waned, Khamenei shifted his support to the religious conservatives.

In 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini had issued a fatwa ordering the execution of the novelist Salmon Rushdie because he considered Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses, blasphemous, and he offered a $3 million reward to anyone who killed Rushdie. Rafsanjani, while he was president, took a less militant position toward Rushdie and his novel, declaring, “an enlightened Muslim should not be afraid of a book.” Nonetheless, Ayatollah Khamenei reaffirmed the death sentence as recently as 2006.

In summer 1995, the Majlis gave the Guardian Council increased power over elections. When the 1996 Majlis elections were held, the Council ensured a conservative victory, even annulling the results in sixteen districts. Still, the 1997 presidential election would change the image, if not the substance, of the government in Iran.

THE REFORMER—Muhammad Khatami was born into a wealthy family in Ardakan in Yazd Province in 1943. His father was a leading ayatollah, but he also listened to foreign radio and followed world affairs. When he was eighteen years old, the younger Khatami became a student of Ayatollah Khomeini in Qom. Unlike other theological students, he declined an exemption from the armed services and spent two years in the army. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Western philosophy and did graduate work in the field of educational sciences. During the struggle against the Shah, he supplemented his religious studies by reading the works of leftist figures like Franz Fanon and Che Guevara. In 1978 the Association of Combative Clergy sent Khatami to Germany to head the Islamic Center in Hamburg. After the Islamic Revolution in Iran, he was elected to the first Majlis, and Ayatollah Khomeini appointed him head of the state publishing company. In 1982 he moved up to be Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance, a position he retained for ten years. Khatami enforced strict censorship and oversaw passage of the restrictive Press Law of 1985. Once the Iran-Iraq War was over he began to relax censorship of the arts.

Disliked by the conservatives for being too permissive, he was forced to resign in 1992. He then served as director of the National Library. He published a book of essays, Fear of Waves, that argued that Islam is superior to Western thought, but that it needed to deal with the modern need for freedom. With this freedom, he said, the West had acquired superior scientific, economic, and political powers. As he stated in 1997, “The strength of the Islamic Revolution stems from the freedom and individual rights that people hold under the Constitution.” Ayatollah Khamenei gave Khatami permission to run in the 1997 presidential election, where he faced the conservative speaker of the Majlis, Ali Akbar Nateq-Nouri. In his campaign, Khatami appealed to women, to young people, and to the ethnic minorities, and he swept to victory with 69% of the vote.

After the election, U.S. president Bill Clinton rewarded the Iranians by placing the MKO on the U.S. government’s list of terrorist groups. Khatami gave a three-hour interview to CNN, and in February the U.S. wrestling team was allowed into Iran to compete in a tournament for the first time since the Islamic Revolution. But the fact that Khatami was the president of Iran and that he represented the will of the majority of the Iranian people did not mean he could successfully pursue a reformist agenda. In October 1998, an election was held for the Assembly of Experts that supervises the Leader. Khamenei announced that, for the first time, non-clerics, including women, would be allowed to run for the Assembly. Forty-six non-clerics, nine of whom were women, took up the offer and signed up to be candidates. Khamenei used the Guardian Council to reject all of them. In fact, the Council disqualified half of the candidates. Not surprisingly, conservative clerics won fifty-four of the eighty-six seats.

In July 1999 university students protested restrictions on the press. Their protests mushroomed into general anti-regime demonstrations, and 750,000 Iranians staged a peaceful march in Tehran. Khamenei was careful in his response and praised the students as “valued members of the nation.” As reasonable as Khamenei was in his words, his actions were a different story. Neshat (Vitality), the third-highest-circulation newspaper in Iran, published an article that challenged capital punishment and the Shari’a concept of eye-for-an-eye punishment. The government suspended the newspaper and sent its editor to jail for thirty months.

In the first round of voting for the sixth Majlis in February 2000, the reformists won two-thirds of the vote. Emboldened, the pro-reform press ran articles about corruption that were popular with the public. The second round of voting was scheduled for May 5. On April 17, the sitting Majlis outlawed criticism of the Leader and of the Constitution. Three days later, Ayatollah Khamenei told a crowd of 100,000 young people that, “Unfortunately, some of the newspapers have become the bases of the enemy. They are performing the same task as BBC radio and the Voice of America.” The following week, the judiciary shut down fourteen reformist publications. Despite these restrictions, the reformists dominated the second round of voting. Again, Khamenei was measured in his verbal response. “The two factions,” he said, “the progressive and the faithful, are as necessary as the two wings of a bird.” But before the newly elected Majlis could meet, the Expediency Council ruled that the Majlis had no authority to investigate any foundation protected by the Leader. In June 2001, Khatami was reelected with 77% of the vote, but he seemed a reluctant candidate, resigned to his fate of being a figurehead with limited power.

THE U.S. RETURNS…AND ELIMINATES IRAN”S MOST HATED ENEMY—When the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks took place in the United States, Ayatollah Khamenei condemned them and said that he would support United Nations-sponsored action against the perpetrators. For his domestic audience, he also condemned the U.S. air strikes against Afghanistan’s Taliban regime, stating that “Terrorism is only an excuse. Why don’t they announce their real intention, their motive for grabbing more power, for imperialism? Since when is it a norm to send troops to another country and hit its cities with missiles and aerial bombardment because of so-called terrorism in that country?”

In reality, Iran had opposed the Taliban from the day it seized power and had consistently criticized the governments of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia for supporting the Taliban. When the Pentagon used Iranian air space during the bombing of Afghanistan, Khamenei and the Iranians did not lodge a protest. It was even reported that Iran had shared anti-Taliban intelligence with the Americans. After the Taliban was driven from power, Iran pledged aid to the new Afghanistan.

On January 29, 2002, U.S. president George W. Bush, in his State of the Union address, included Iran in his tripartite “Axis of Evil,” accusing the Iranian government of building weapons of mass destruction and of exporting terrorism. The Iranians were shocked to be lumped together with their number-one enemy, Saddam Hussein, and with North Korea, and Bush’s speech was particularly disheartening to the reformers in Iran who had been trying so hard to reestablish cordial relations with the West.

When the United States invaded Iraq in March 2003, the Iranians were not pleased by what they saw as the beginning of a permanent American military presence to their west, complementing the U.S. bases to their east in Afghanistan. On the other hand, they were delighted by the removal of Saddam Hussein, the man they held responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of their people. In addition, the Americans insisted that Iraq hold democratic elections, which meant that Shiites, being the majority in Iraq, would dominate the new government. At the very least, Iranian Shiites would have freer access to the Shiite holy places in Iraq. In April 2004, the Bush administration accused Iran of inciting unrest in Iraq. Ayatollah Khamenei was contemptuous of this accusation. “There is no need for incitement,” he said. “You yourself are the biggest and dirtiest provokers of the Iraqi nation.” When Shi’a uprisings broke out in Iraq, tens of thousands of Iranians marched in support of their fellow Shiites.

THE NON-REFORMER—As the 2005 presidential election approached, Khamenei and the conservative clerics faced a challenge. They had successfully survived eight years of Muhammad Khatami’s reformist rhetoric while preventing him from making any serious changes to society, and it was clear that they could continue to keep control as long as the Guardian Council and the Leader retained veto power over the actions of the president, the Majlis, and the judiciary. Yet it would be better if the president was a man who, although loyal to the conservatives, could appeal to young people and the poor in the same way that Khatami had. They chose Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a relatively obscure politician, who was a protégé of Ayatollah Khamenei and a follower of the extremist Ayatollah Muhammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi.

Born the son of a blacksmith in Garmsar in Semnan Province in 1956, Ahmadinejad attended the Iran University of Science and Technology, eventually earning a PhD in engineering and traffic and transportation planning. His involvement in the 1979 revolution is somewhat murky, but it is believed that he argued in favor of supplementing the takeover of the U.S. embassy with a simultaneous occupation of the Soviet embassy. During the Iran-Iraq War, he joined the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and is alleged to have been involved in covert operations in Kirkuk, Iraq. He also served as an engineer in the army and as a basiji, one of the religious militia enforcing cultural restrictions. After the war, Ahmadinejad served the government in West Azarbaijan Province, and in 1993 he was appointed governor of the newly created Ardabil Province in the northwest.

In 2003, the city council of Tehran chose Ahmadinejad to be the city’s mayor. He immediately set about imposing hard-line policies, such as creating separate elevators for men and women in city offices. As mayor, he was also in charge of the daily municipality-owned newspaper Hamshahri. When a Hamshahri journalist asked President Khatami about the existence of illegal parallel intelligence agencies, Ahmadinejad fired the journalist. Nonetheless, Ahmadinejad so angered Khatami that the president barred him from attending cabinet meetings, a privilege normally accorded to the mayor of Tehran.

Khamenei tapped Ahmadinejad to be the establishment candidate for president in 2005. His campaign motto was, “It’s possible and we can do it.” He pledged to put “the petroleum income on people’s tables,” a reference to the widespread belief that the nation’s wealth was not filtering down to the common people. For the most part, Ahmadinejad sold himself as a man of the people who lived a modest life in a modest home. Relatively young for an Iranian leader, he did in fact cut into the youth vote that had previously supported reform. He finished second in the opening round of voting and then won the runoff.

Assuming office on August 14, 2005, Ahmadinejad soon attracted the attention of the outside world with comments that played well inside Iran but sounded outrageous outside the country, particularly in the non-Muslim nations. For example, he called for Israel, which he referred to as a “disgraceful blot,” to be “wiped off the map,” a demand that he later moderated by suggesting that it be moved to “Europe, the United States, Canada, or Alaska.”

Ahmadinejad gained domestic support when the West demanded that he shut down Iran’s nuclear program. He claimed that his country was only interested in nuclear power and that nuclear weapons were “against our religion.” “A nation,” he explained, “which has culture, logic and civilization does not need nuclear weapons.” Khamenei’s reaction to Ahmadinejad was mixed. After all, it was Khamenei, not Ahmadinejad, who controlled Iran’s nuclear policy, as well as all aspects of foreign relations. As long as Ahmadinejad did not develop too great a personal support base, Khamenei seemed satisfied to let him speak his mind and draw attention away from the real decision makers. Still, to be on the safe side, in September 2005, Khamenei expanded the power of the Expediency Council, which was still headed by ex-president Rafsanjani.

|

A SHORT GUIDE TO THE IRANIAN GOVERNMENT: THE PRESIDENCY—The president is not entirely a figurehead, but he has limited power.

THE LEGISLATURE—The Majlis, also known as the Islamic Consultative Assembly, has 290 members who serve four-year terms. Like the president, their powers are limited

THE JUDICIARY—The judicial branch is independent—except that the Leader can overrule anything it does.

THE COUNCIL OF GUARDIANS—Made up of twelve members and headed by the Leader, the Council screens all prospective candidates for all elected offices including members of the Majlis, the Assembly of Experts, and the president. Six of the members are appointed by the Leader and six are chosen by the head of the judiciary, who is himself appointed by the Leader.

THE ASSEMBLY OF EXPERTS—The Assembly selects and supervises the Leader. Its eighty-six members are elected by the public for eight-year terms.

THE EXPEDIENCY COUNCIL—Consisting of twenty-five members, the Expediency Council mediates disputes between the Majlis, and the Council of Guardians. The Leader sets its agenda.

THE LEADER—Known in Iran as the Rahbar and often, for effect, as the Supreme Leader, the Leader can overrule any decisions made by the president, the Majlis or the judiciary.

|

EXECUTIONS—The Islamic Code of 1982 authorizes the death penalty for a range of crimes that includes rape, adultery, sodomy, and the habitual drinking of alcohol. The law was amended in 1989 to include death for possession of specific drugs, including thirty grams of codeine or methamphetamine. The Code goes into detail as to how executions are to be carried out. For example, it states, “In the punishment of stoning to death, the stones should not be so large that the person dies on being hit by one or two.”

People convicted of premeditated murder are subject to the death penalty, but there is one exception. If a Muslim kills a member of a religious minority, his crime is not punishable by death. Most political executions are of minorities, usually Kurds and Baluchis. Apostasy, the rejection of Islam in order to switch to a different faith, is considered a capital crime. In one unusually outlandish case, an Iranian citizen, Mehdi Dibaj, was sentenced to death on December 3, 1993, for apostasy—forty-five years after he converted to Christianity. He was a minister in the Assemblies of God. After appeals from the United Nations and the Vatican, among others, Dibaj was released from prison, but he was found dead a few months later. The murders of other Protestant clergy followed.

During the 1990s, the Iranian government carried out dozens of assassinations overseas in a program run by Mustafa Pour-Muhammadir. On September 17, 1992, an Iranian agent and four hired gunmen from Lebanon burst into the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin and shot to death four Iranian Kurds. Four and a half years later, a German court convicted the agent and his Lebanese accomplices for the murders. While no members of the Iranian government were charged in the case, the court concluded in its written opinion that the defendants had no personal motive for their crime and acted upon an "official liquidation order" issued by senior Iranian officials.

PUNISHING CULTURAL CRIMES—Created by Ayatollah Khomeini, the basijis are an irregular militia in charge of cracking down on cultural crimes. In 1989 and 1990, 5,200 young men and 3,500 young women were arrested in Tehran for such “crimes” as “illicit relations between boys and girls and married men and women.” Some women were arrested for “exhibiting corruption on the streets,” which is to say wearing makeup or sunglasses or not wearing a headscarf. In a typical case, basijis arrested twenty-eight young men and women between the ages of seventeen and twenty at a private party because they were in possession of videocassettes of “repulsive” (i.e., Hollywood) movies. They received fines and ten lashes and three were sent to prison. Mixed-sex wedding parties, at which men and women celebrate in the same room, are also sometimes forbidden. In one notorious case in 1995, 127 of 128 guests at a wedding celebration were fined or flogged. The bride received eighty-five lashes and the father of the groom spent eight months in jail. The only guest who was spared was a child.

CENSORSHIP AND EXTREME CENSORSHIP:

- The bounty that Ayatollah Khomeini placed on Salmon Rushdie in 1989 for writing the novel The Satanic Verses became an international cause célèbre, but Rushdie is not the only novelist to incur the wrath of Iran’s leaders. In 1990, the woman novelist Shammush Parsipur was charged with, among other things, writing a dialogue about virginity in her book Women Without Men.

- Satellite dishes were banned in March 1995, but their use is widespread anyway. Government-approved television is so religiously oriented that Iranians nicknamed it “mullahvision.”

- In July 1998, the Press Court revoked the license of the magazine Jame (Association) because it published a photograph of young Iranian men and women dancing in celebration after Iran’s victory over the United States in the World Cup soccer tournament.

- In November and December 1998, the Intelligence Ministry assassinated several writers and dissident politicians.

- On July 7, 1999, the Majlis amended the 1985 Press Law to allow the Press Court to overrule jury verdicts. The next evening, 500 Tehran University students were attending a meeting about the closure of newspapers when they were attacked with rubber clubs by 400 vigilantes, while members of the Law Enforcement Forces watched. An off-duty soldier attending the meeting was killed. President Khatami was so incensed that he ordered the arrest of 100 of the perpetrators. Protests spread around the country, leading to 1,000 arrests, the closing of the university, and a journalists’ strike. Khamenei blamed the United States for the entire affair.

WOMEN—After the 1979 revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini encouraged procreation and even lowered the marriage age for females from eighteen to nine. The drive to increase the population worked so well that in 1993 the government went in the opposite direction, decreeing an end to paid maternity leave for mothers who gave birth to more than two children. Couples were also required to attend contraception classes before getting married. Khomeini, who had drawn on the support of women before the revolution, turned against them after he took power. In addition to imposing a dress code, he declared that a wife must submit to her husband in all matters, including sex. In case of a divorce, which a husband could obtain by simply stating that he wanted one, the husband gained custody of the couple’s children. The Family Law of 1998 eased some restrictions. Men had to go to court to obtain a divorce and if a man petitioned for a divorce without his wife’s consent, she was entitled to half of the couple’s property. However, women still had to sit in the back of buses; they could not travel without their husband’s written permission; and in court their testimony was worth half that of a man.

KHAMANEI SPEAKS:

“Our importance around the world and in the eyes of other people is based on our standing up to America.”

November 7, 1997

“The epoch of adhering to Western prescriptions has passed. The enemies of Islam are seeking to separate religion from politics. Using seductive Western concepts such as political parties, competitive pluralist political systems and bogus democracy, the Westernized are trying to present a utopic picture of Western societies and portray them as the only salvation for our Islamic society.”

July 24, 1998

-David Wallechinsky

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Musk and Trump Fire Members of Congress

- Trump Calls for Violent Street Demonstrations Against Himself

- Trump Changes Name of Republican Party

- The 2024 Election By the Numbers

- Bashar al-Assad—The Fall of a Rabid AntiSemite

Comments