Guantánamo Defense Attorney Wants Tribunal Site Tested for Toxic Chemicals

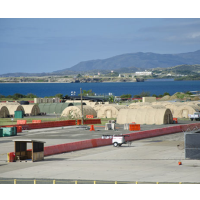

Camp Justice--Credit: Department of Defense

Camp Justice--Credit: Department of Defense

By Britain Eakin, Courthouse News Service

FT. MEADE, Md. — A 9/11 defender told a military judge Thursday he can find no other example that mirrors the Guantánamo war court — an abandoned airfield tainted by fuel spills and toxic chemicals transformed into a court.

“This is weird,” Air Force Capt. Michael Schwartz, the senior defense attorney for suspected 9/11 plotter Walid bin Attash, said of his request for the court to fund a toxicology expert to determine if the court is safe to work in.

That there are no other toxic air fields-turned-war court examples is not the only strange thing about the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, but it highlights the often unchartered legal waters that the Guantánamo war court proceedings sometimes wade into.

“Yes, this is highly unusual in terms of litigating a resource for a toxicologist to determine the safety of the courtroom, but it’s just the nature of where we are,” Schwartz said, calling the motion “odd.”

“You and I agree on that,” Judge Army Col. James L. Pohl responded during the hearing, which the Defense Department showed in a closed-circuit feed at Ft. Meade, Maryland.

Questions about the safety of the compound have loomed over proceedings since reports emerged last July that seven case workers had developed cancer. The United States built the multimillion dollar legal compound to carry out Guantánamo war tribunals next to an abandoned Navy airstrip on an area once used to dump jet fuel.

After the cancer-cluster allegations arose, the government found unsafe levels of arsenic, mercury, formaldehyde and other carcinogens in testing samples, but Schwartz says it will not identify the precise locations where those samples were collected for security reasons.

The government has since said the Camp Justice war court compound is safe, and the prosecution says any ruling on the issue is outside the purview of the military commission’s efforts to try the five suspected 9/11 plotters, including its self-proclaimed mastermind, Khalid Shaikh Mohammad.

A Feb. 23 Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center report, however, did not issue an opinion on the compound’s safety because more testing needs to be done.

“On its face, the information we have at our disposal now, the information from the government in the 23 February report and a variety of other interim updates, does not stand for the proposition that Camp Justice is safe,” Schwartz said.

Schwartz says a toxicology expert can help interpret the government’s underlying data and sampling methodologies to determine if the government’s claim that the compound is safe passes muster. However, the government has yet to provide 9/11 defenders with the information Schwartz says their expert would need to rely on. If the government refuses to hand over the data, the defense expert might need to conduct some analysis, Schwartz said.

Schwartz told Pohl the defense is not currently challenging the government’s claim that Camp Justice is safe, though he said the defense could do that in the future. He is simply asking for the resources to fund an expert.

“So you want me to provide you expert assistance because you might have a disagreement with something you currently do not have a disagreement with because you don’t have enough information to know whether or not you disagree or not?” Pohl asked.

“That’s exactly right, and it’s simply because the process has been so unusual and so irregular,” Schwartz responded.

The defense team did not learn about the Feb. 23 report until April, something Schwartz reminded Pohl of. That report contained information about unsafe levels of formaldehyde in naval base housing — the Cuzcos — where defense staff stays.

“For the next five weeks we continued to send down our team, our people, to stay in the Cuzcos while the Public Health Center knew that the levels of formaldehyde could be making the occupants sick. That’s a very good reason to question the regularity of this report and this analysis,” he said.

Schwartz hinted that the Public Health Center may have fabricated data on a slide it issued to help explain the February 23 report, which showed that Florida has higher levels of arsenic in its soil than what was found at Camp Justice. Schwartz said a quick Google search contradicted that assertion.

Pohl questioned whether the issue could be properly brought before the military commission. The prosecution team says it cannot.

“If we knew that there was a bomb sitting under this podium right now, there’s no way that the judge couldn’t do something about that,” Schwartz had said earlier.

But Chief Prosecutor Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins argued that Pohl should reject the request, telling him the Camp Justice compound is safe to live and work in until the Public Health Center completes its testing.

“This commission should not be turned into a process for safety and industrial hygiene,” Martins said.

The Navy is doing its job competently, impartially and professionally, he added.

“We simply do not have clear evidence to the contrary here. None of the examples cited by counsel even approach this level.”

Pohl said he would consider the defense request “and issue a ruling in due course.”

To Learn More:

Congressional Republicans Fight Hard to Keep Guantánamo Open Forever (by Noel Brinkerhoff, AllGov)

Pentagon’s Exiting Guantánamo Prison Architect Reverses Position on Detainee Policies (by Noel Brinkerhoff, AllGov)

Military Defense Attorneys Clash with Guantánamo Commander about Reading Mail (by Noel Brinkerhoff and David Wallechinsky, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Musk and Trump Fire Members of Congress

- Trump Calls for Violent Street Demonstrations Against Himself

- Trump Changes Name of Republican Party

- The 2024 Election By the Numbers

- Bashar al-Assad—The Fall of a Rabid AntiSemite

Comments